“It’s Always the Fixer…”

I first sought out Jon Swain to interview for my trilogy of “Journos” episodes, but we didn’t connect in time. I include here some of Jon’s thoughts on what life was like for journalists in Cambodia in the 1970’s. Episode 12 of the podcast is below.

To see some of Jon Swain’s stories for The Sunday Times from April 1975 in Phnom Penh, please go to the blog.

“The Killing Fields” is a seminal movie. That’s partly because it is so shockingly accurate. In addition to the acting of Haing Ngor, who survived the Khmer Rouge, the film’s source material came from Sydney Schanberg and was informed by other journalists who actually lived those moments in history.

For the next two episodes, I’m speaking with journalist Jon Swain and photographer Roland Neveu. Along with Ngor, they were the only two people who were both in Phnom Penh in 1975 when it fell to the Khmer Rouge who were also on the set during the making of the film.

Welcome to Episode 12 of “Who Killed Haing Ngor.” This is my real-time and crowdsourced podcast in which we explore lingering questions about the murder - and the legacy of Dr. Haing S. Ngor. Best known for his role in “The Killing Fields,” he was also a humanitarian and a businessman.

This episode also brings us a closer look at at Dith Pran – a so-called “fixer” - whose courage and heroism are what “The Killing Fields” is all about.

It’s one of the defining scenes in “The Killing Fields.” Journalists Jon Swain, Sydney Schanberg and photographer Al Rockoff are captured by the Khmer Rouge, and forced at gunpoint into an armored personnel carrier.

This is Jon Swain. He’s a veteran foreign correspondent, who was with the British newspaper, The Sunday Times, for 35 years.

SWAIN: “We were put into an armored personnel carrier and driven to the banks of the Mekong, where we had to disembark and they were going to shoot us and throw our bodies into the water. And these were young Khmer Rouge soldiers - peasant soldiers. You know, the oldest was 14 or 15 years old. They were - they were disciplined but at the same time out of control and if they were told to shoot someone, even then they get to just word without second thought.

They may well have been shot, except for one thing. Dith Pran, who was Schanberg’s “fixer” for “The New York Times,” talked his way into the APC . That was a breathtakingly courageous thing to do. Then – he just kept talking.

SWAIN: He was told by the Khmer Rouge commander not to get into the armored personnel carrier with us because he was a Cambodian - and that we were being taken away, as Westerners, and would suffer the fate of that they decided. And they didn't want him around. And he just insisted. And the way he talked his way into the armored personnel carrier, I can never forget because he was both humble and assertive, in a way. He obviously was speaking Cambodian - Khmer - but he knew the Khmer Rouge vernacular very well, so he could chat with them the way they talked to each other.

Swain, Schanberg and Rockoff had nothing to do but wait, while their fate was being decided in a language they largely couldn’t understand. For the record, the Khmer Rouge hated Americans, which Schanberg and Rockoff were.

MPN: Did Dith Pran tell you afterwards? What was the tone of his rationale - like, Don't kill them, they're French. Or, Don't kill them. We need people to report on the great revolution.

SWAIN: It was very much what you just said. It was: these Westerners are in Cambodia to report on the revolution. It was very much that. They're not here fighting, or they're not Americans. They're here doing a proper job of reporting on the revolution - what you've achieved.

Pran’s artful persuasion appealed to Khmer Rouge egos, it sowed enough doubt, and it bought enough time until a more senior Khmer Rouge officer came along. He recognized the journalists for the non-combatants they were. He ordered Swain, Schanberg and Rockoff to be released - and told them to get to the French embassy, where Phnom Penh’s remaining Westerners had sought shelter.

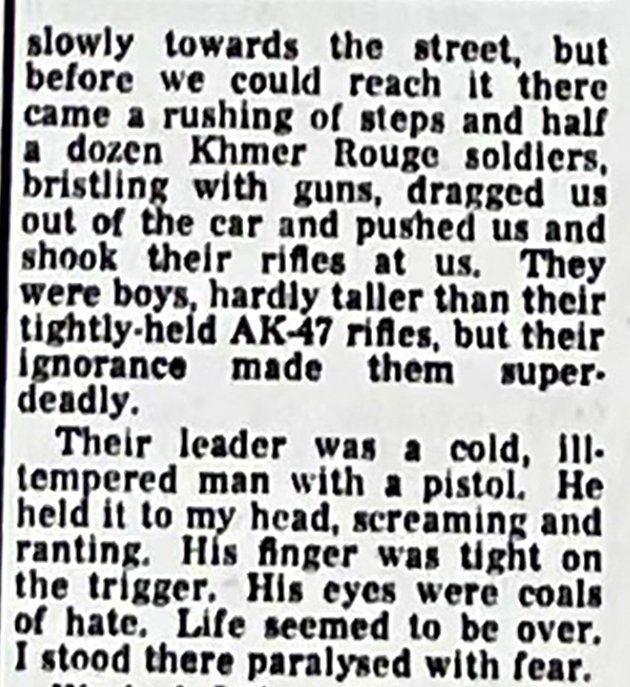

These are highlights of Jon Swain’s “Diary of a Doomed City,” a 5 page spread in The Sunday Times, in which he charted the Fall of Phnom Penh. The full story — and other of Swain’s stories from Phnom Penh for The Sunday Times — are available here.

Dith Pran was a fixer. That’s the colloquial term for an interpreter, guide and logistics pro hired by western news organizations to help correspondents and television crews report from foreign lands. Some fixers are actually reporters for local news organizations who moonlight for the international press.

Personally – having been one – I find the term “fixer” somewhat denigrating. It denies people their editorial credit. To me, the better terms are “assistant reporter,” “local producer,” or “national producer.” Things along those lines.

That’s especially considering how people like Dith Pran punch way above their weight by scoring the interviews and handling the war-zone travel that determine editorial coverage – the actual situations the correspondent sees and writes about. Think about it: Sydney Schanberg won the 1976 Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting for his Cambodia coverage.

Jon Swain agrees about fixers, and the contribution of Dith Pran.

SWAIN: Having been a tour operator - a tour guide in Siem Reap - before the war he knew how to handle Westerners, anyway, and he knew his country backwards, and he knew how to get to places that Sydney or other Western journalists might not be able to. He really was a help to Sydney. I don't think without him, Sydney would not have done the journalism that he was known for.

Schanberg knew it, too. When he accepted the Pulitzer Prize, he shared credit with Dith Pran.

One thing I just want to make clear is that what Dith Pran did - talking his way into that APC - was extraordinary, but it was also not exceptional. Fixers risk their lives to save their Western colleagues with shocking frequency.

In 2009, in Afghanistan, someone I’ll call “assistant reporter” Sultan Munadi was kidnapped alongside journalist Stephen Farrell, a Brit, working for “The New York Times.” British commandos staged a rescue, which turned into a firefight with militants. As they escaped, Munadi rushed ahead of Farrell, shouting, “Journalist, journalist!” He was shot and killed.

Munadi’s death may have been bad luck. But it looks to me like a disproportionate sense of responsibility toward keeping his foreign colleague safe that made Munadi leap ahead.

The incident prompted George Packer of “The New Yorker” to write a column entitled, “It’s Always the Fixer Who Dies.” Munadi’s death, he noted, was simply the latest in a long-running trend – one that’s carried on into Ukraine. Links are on the webpage.

Most correspondents I know are decent human beings, and I’d certainly like to think that of myself. I, too, hire fixers. But there’s still a wicked power imbalance within the world of international news: when things get tough, the fixer feels responsible; the foreign correspondent gets to leave.

SWAIN: As Sydney said at the time and you know, we all realize, you know, Pran has saved our lives.

And in one sense, that power-imbalance is what “The Killing Fields” is all about.

ROLAND NEVEU: I spend some time around the pool at the Royal Hotel, the Phnom, trying to find out from the interpreter, from the driver, and from the you know, the younger guys. I would talk some time to Jon Swain, which was more younger and more available, in a way and some other people. So you do build up your network of information - because safety I mean, you need to know what's happening and you need to know where to go.

This is Roland Neveu, a French photographer. He began covering Cambodia as a university student. He went back in 1975, a few weeks before the Khmer Rouge seized power.

Talking to Roland and Jon, it’s clear to me how much “The Killing Fields” gets right, and how little has changed since the 1970’s. In dangerous situations - like Baghdad, for example – the press ends up congregating in one or two hotels, for safety. In 1975 Phnom Penh, it was the Royal.

War-time hotels are rumor mills, often driven by hyper-competition. They’re also remembered with intense nostalgia for the camaraderie of the press corps, who risk their lives to report the news.

Remember from episodes 4, 5 and 6 – my “Journos” trilogy - Cambodia was incredibly dangerous for reporters. In just eight weeks in 1970, 20 journalists went missing, out of a press corps of about 60 – a 30 percent casualty rate.

SWAIN: Most of us stayed in one hotel, the Hotel Royal. So we used to do a sort of daily count of journalists as they go out and as they come back, when someone had disappeared it did send a real -- I mean, the atmosphere in the hotel which used to be quite jolly - changed that evening, thinking about our comrades, you know. Before that we've been drinking around the pool and relaxing after a day a covering the war or writing our stories. And then a couple of hours later we'd know that one of our colleagues was missing and we soon learned that they were dead.

MPN: So was Dith Pran one of the people you would chat up for information?

NEVEU: Not really because we knew that “The New York Times.” This guy is not going to tell you anything unless you're a friend. So I didn't have time to befriend a guy like this. So, but I would learn some stuff from Rockoff.

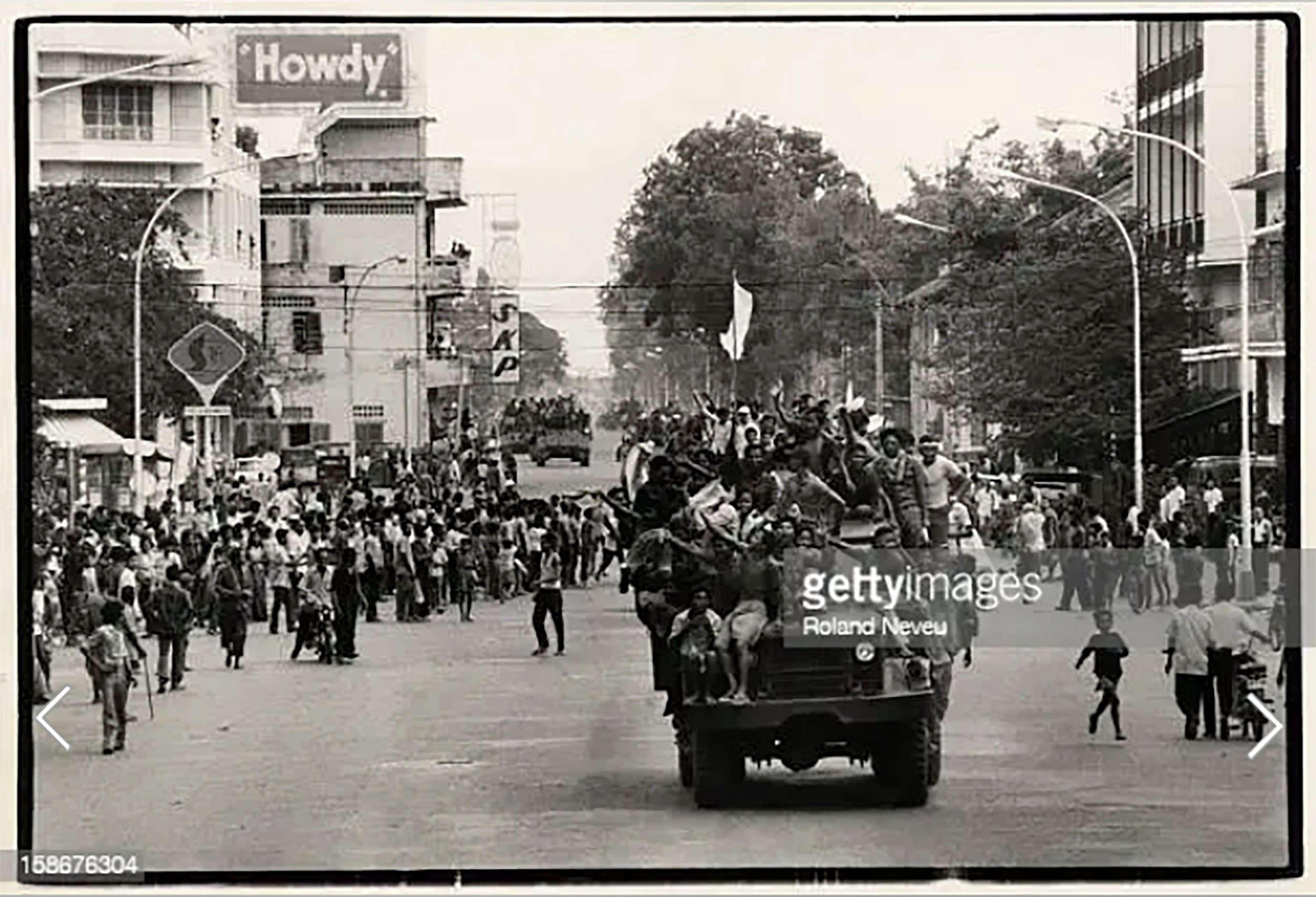

Roland’s book, “The Fall of Phnom Penh” is a wonderful collection of photos from April 1975. As a feral freelancer myself, I appreciate reading the calculus to Roland’s coverage - eyeing up the Khmer Rouge in this part of town, the constant measuring of what he could get away with.

Roland’s given me permission to post some of his shots on whokilledhaingngor.com. There are some great ones.

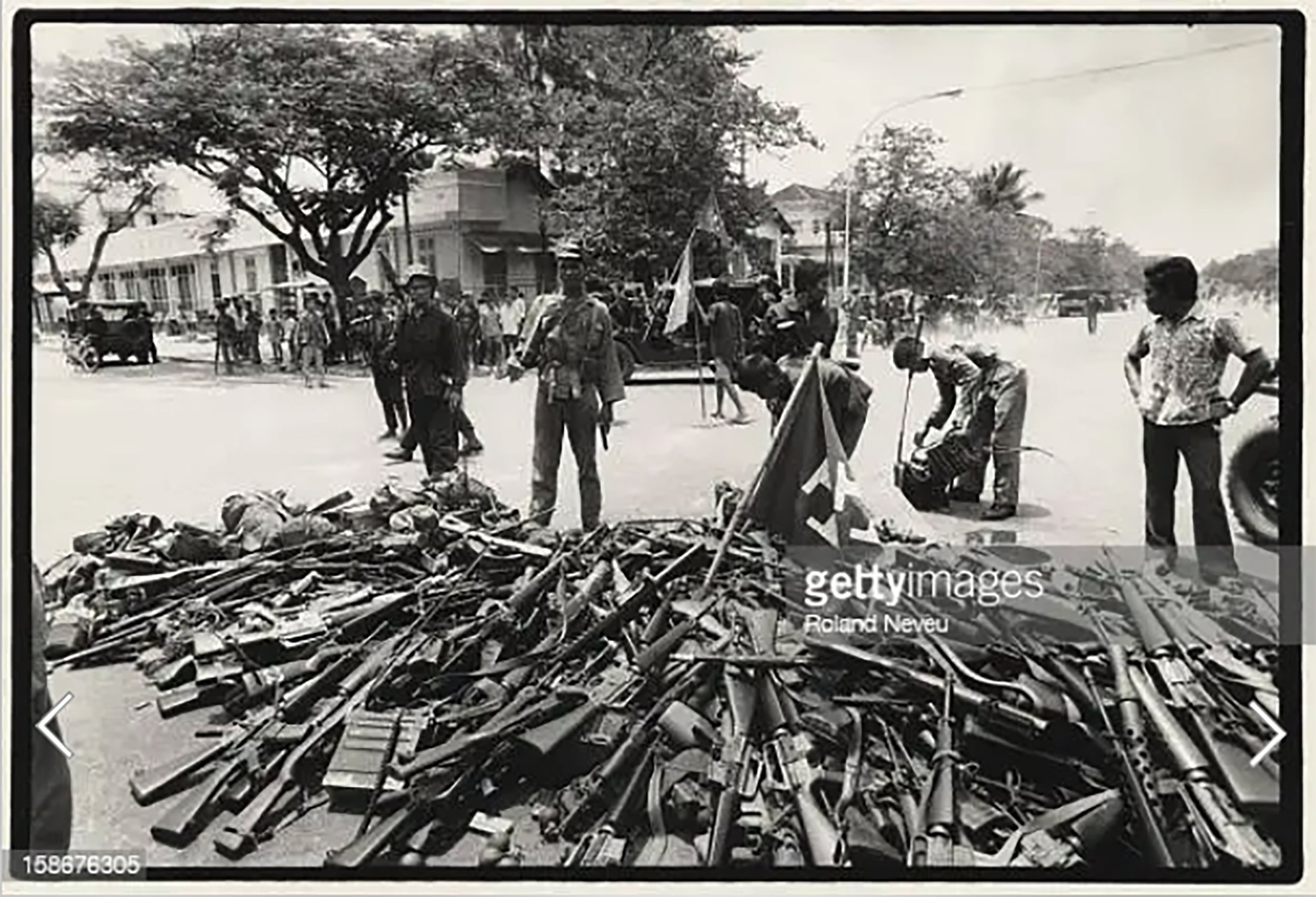

USE THE UPPER ARROWS TO SCROLL Photos courtesy of Roland Neveu. Read more about him here and here.To see more photos of the fall of Phnom Penh, or to purchase, please click here. These photos show victorious Khmer Rouge troops forcibly evacuating Phnom Penh; the Hotel Royal, and government soldiers and civilians surrendering arms to the Khmer Rouge.

As I said, as the Khmer Rouge gained total control over Phnom Penh, everyone ended up at the French embassy. Cambodia used to be a French colony, so that diplomatic ground still held some sway with the Khmer Rouge.

This brings us to another infamous scene in “The Killing Fields.” It’s also the one that’s the most controversial. What really went on with that fake passport?

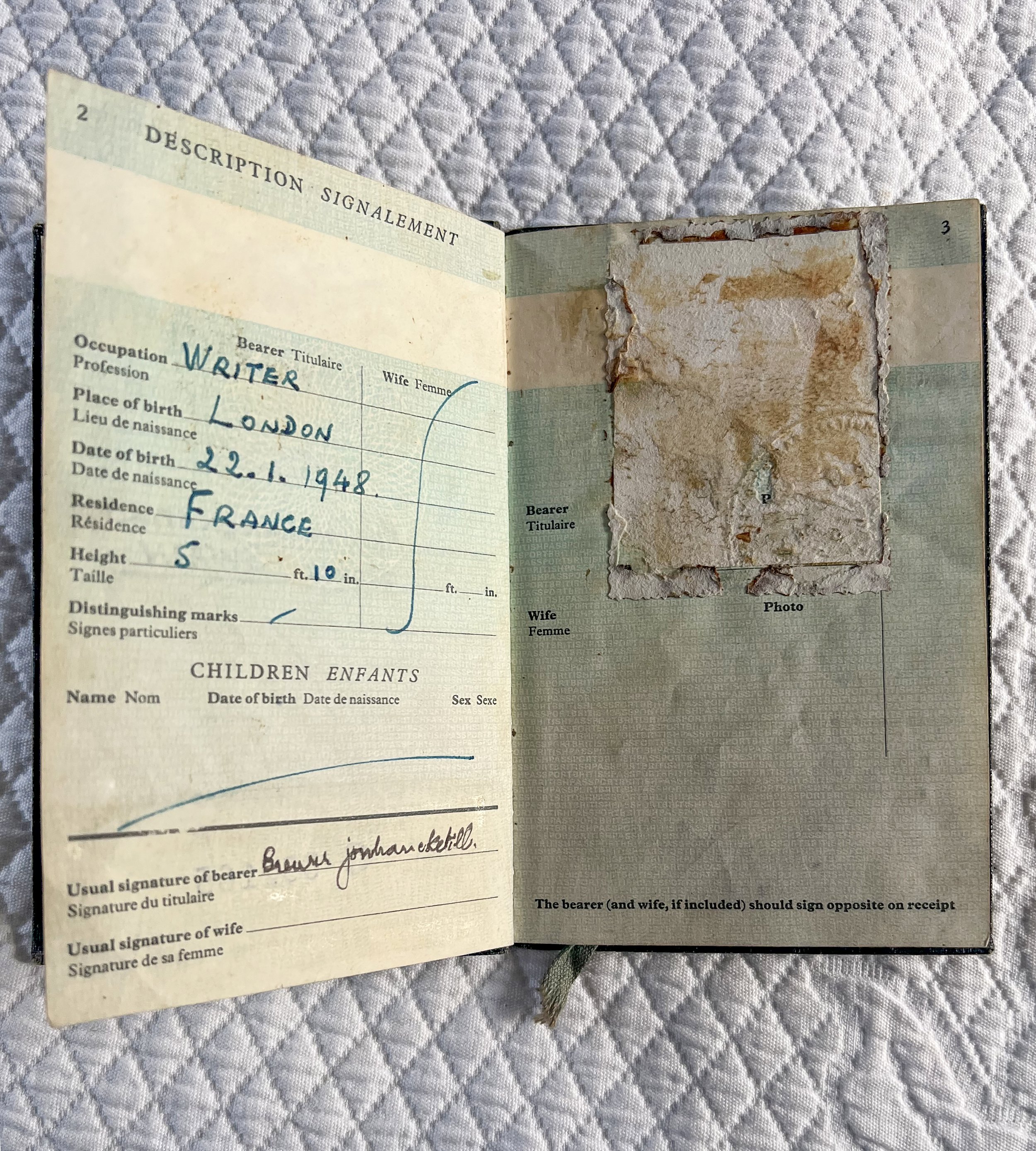

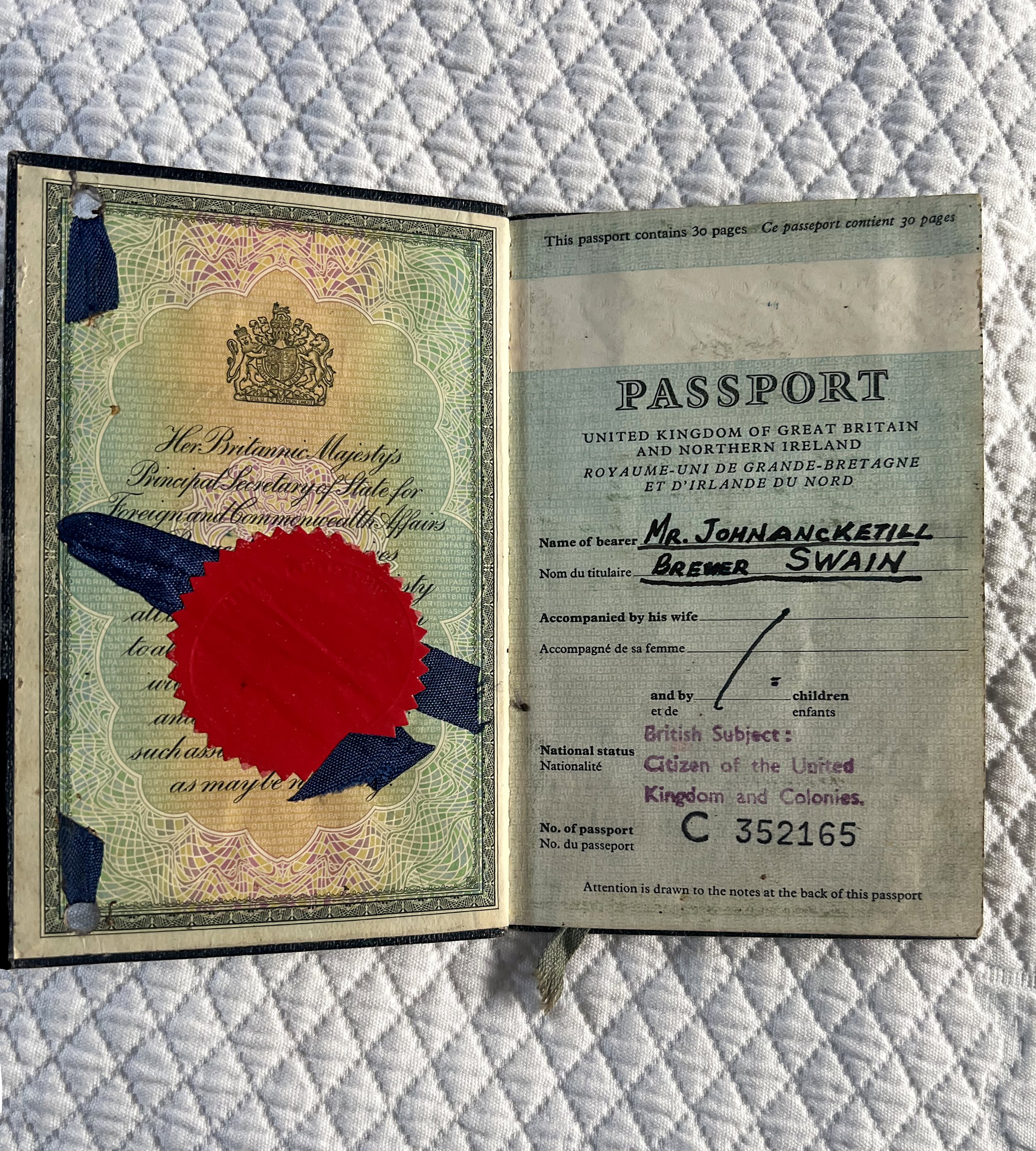

Jon Swain generously sent me photos of his 1975 passport(s) - including the actual one he, Al Rockoff and Sydney Schanberg cannibalized to make a fake passport for Dith Pran. As Jon says, Looking at it again I can see it's a rotten forgery but they were desperate times and we wanted to save Pran from having to leave the embassy to what seemed a certain death at the hands of the Khmer Rouge at all costs; it seemed to be the only way to keep him with us. No wonder the French embassy officials saw through the forgery and rejected our efforts as putting everyone in the embassy at risk.

The French embassy was all but overrun. Hundreds of people - Cambodians and foreigners alike – were camped out on the grounds, or claiming nooks in hallways and offices. No one knew what was going to happen next, but the war had been pretty bloody so far.

Then, the Khmer Rouge ordered all Cambodians and other Asians to leave the embassy. Only those with Western passports were allowed to stay.

Schanberg had previously arranged for Dith Pran’s wife and children to be evacuated. This is a clip I’ve swiped from an ABC News Prime Time Live broadcast from 1989 – that we’ll come back to in the next episode. (Sorry, ABC – but you’ve done worse.) It’s the real Dith Pran.

DITH PRAN: “Sydney told me that – hey - you go or not? Now! I said, I don’t want to go, I’d like to stay behind, but please take my family.”

History was happening. Dith Pran worked in journalism so he may have wanted to cover the end of the story. But as Jon’s going to tell us shortly, he was also motivated by loyalty -- and that outsized sense responsibility.

Fast forward, and now - Pran was going to be forced out of the embassy. So Jon, Schanberg and Rockoff tried to make a fake passport.

SWAIN: Yes, it was my idea I had a - those old British passports - which were in blue and made of cardboard - if you filled up one passport, but the passport was still valid, the embassy which you took it to, to renew would cancel that passport and stick another passport on top of it. So I actually had four passports on top of each other because I had so many visas in them, and the passports were still valid. So I ripped off one of them.

Jon’s been kind of enough to send me photos of his old passports – the ones they tried to doctor. They’re on the webpage.

They weren’t the only ones trying to make fake ID’s. French officials were at it, too. Roland heard the rumors, en français.

NEVEU: I also understood that the French consulate had some blank passports, and they gave away some blank passports. They didn’t want the rest of us to see, of course. This is the job of a consulate – they always have extra passports on hand, in case. So I think they used what they had. It should be a few dozen.

Neither Jon nor Roland know all the details. But with those quickie passports, French officials probably rescued just Cambodian women, who could be passed off as Frenchman’s wives.

Meanwhile, Jon thought Dith Pran could pass for a Nepali. Nepal was once part of the British empire. So it would be plausible for this Asian man to have a British passport and a Western name.

SWAIN: We doctored my name, which is a funny English name Jon Ancketill Brewer Swain. And using a mixture of rice water - I suppose just rice mixed with water - we actually scrubbed out my name on the front page of the passport. And Pran wrote in “Ancketill Jon Brewer,” rather than Jon Ancketill Brewer Swain. We fiddled around with it.

Here's the controversial part.

SWAIN: Fortunately Pran actually had a passport of a photograph of himself which fitted - was of that size. So we took a razor blade and peeled off my photograph and using a mixture of rice and water as a glue, we stuck Pran’s picture on top of it. That's isn’t how - what's shown in the film.

MPN : Do you keep up with the real Al Rockoff?

SWAIN: Yes, yes. Al got very cross because he was saying as in the film, the photograph he allegedly took, disappears or fades, fades in the development. And he got very angry about that, because he said he'd been portrayed as a bad photographer because he couldn't develop pictures - and complained. But it was done for dramatic effect.

“Angry” doesn’t begin to describe it. The real Al Rockoff is a friendly acquaintance. He’s been incensed about “The Killing Fields” since the film came out nearly 40 years ago. He felt badly maligned by what is, in fact, an entirely fictitious scene. He has so far declined to be part of this podcast. For the record, I’d also have loved to interview Dith Pran and Sydney Schanberg, but they’ve both passed away.

MPN: So then if it was a real photo that you swiped from a different identity card, why was the passport rejected?

SWAIN: It didn’t look very realistic to the French officials when we handed it in. And they came over and talked to me and talked to Sydney and said, “Look, this won't do. Your fake passport, so to speak, will instantly be recognized as such by the Khmer Rouge. And you'll be threaten the rest of you have threatened the rest of the people in the embassy. So we won't accept it.” So that's why Pran decided to leave because there was nothing else to be done.

Roland was among those who bore witness to the scene when the Cambodians and other Asians were forced out of the embassy. He describes the atmosphere:

NEVEU: Apprehension - but no choice. There’s a situation… They control you. So that’s it. You are caught. You have no choice. That's the kind of situation. I mean, that's it. You have to go, there to go. Some people were crying, of course, I mean, not really that much because Asians - I mean, the fatalistic side is a little higher than for the Westerners, for example. So people just said, OK. You give it to the gods in a way. So that's it, you know?

Eventually, the Khmer Rouge organized some trucks. They drove the remaining Westerners who had been holed up in the embassy overland to Aranyaprathet, where they were welcomed into Thailand.

The holocaust that was the Khmer Rouge reign over Cambodia was just beginning. What started for Sydney Schanberg was a different kind of hell, captured well in the film.

SWAIN: All the films on Vietnam - Cambodia being part of the Vietnam War, I put them together -- all the films American films or Hollywood films - have been about, to my mind, about, We Americans are fighting a dreadful war in Vietnam. Look, what it has done has done to us. And this film, was a breakaway from that. It was a film about guilt and loyalty, by an American correspondent who felt very guilty about not being able to protect his Cambodian fixer, Dith Pran. And Pran’s loyalty to Sydney Schanberg, the American journalist, which persuaded him to stay behind in Phnom Penh, risking his life because his boss wanted to stay, or decided to stay. And Sydney was overcome with guilt with that and the next four years he spent his time trying to find out whether Pran had survived going into the killing fields when he was thrown out, when he left the embassy, and we tried to protect him.

And that side of the film I think resonates with the Western audience very strongly about a Westerner feeling guilt and the loyalty of that episode. And that the second half of the film is about Cambodians doing horrible things to Cambodians. And if it had just been a film about Cambodians doing horrible things to Cambodians, I don't think it would have had the impact that it had. It was the mixture of the two, which were beautifully fused and so that an international audience could identify with it in many different ways.

Remember, “It’s Always the Fixer Who Dies.”

Thank you for listening. My name is M.P. Nunan

One quick addendum - Jon Swain has sent me some of his articles from 1975 for The Sunday Times, and I'll post them on the webpage. So you can check those out and the photos by Roland Neveu, on whokilledhaingngor.com

In the next episode, I talk with Jon Swain and Roland Neveu about their experiences when the film was being made. Along with Haing Ngor, they were the only people on the set who had been in Cambodia in 1975. We’ll also hear about their impressions of Ngor.

Remember, this is a crowd-sourced podcast – an experiment in journalism.

If you knew Haing Ngor personally and would like to contribute – even just an interesting anecdote - please get in touch. If you know any details about his murder you think are relevant, please get in touch. The best way to reach me is to email whokilledhaingngor@gmail.com

Haing is Ha I ng. Ngor is N G or

Thank you again.