Art Imitates Life… Then Changes It

Art, it’s been widely said, imitates life. But there are also moments when it changes it.

The impact of “The Killing Fields” was so profound, that some credit it with helping launch Cambodia’s peace plan, ending decades of civil war.

Photos courtesy of Roland Neveu. In the first, Haing Ngor on the set of “The Killing Fields.” The second is a group shot on the set of “The Killing Fields,” with Sam Waterston, Julian Sands, a script assistant; producer Sir David Puttnam; unknown (standing); John Malkovich, and Haing Ngor.

Welcome to Episode 13 of “Who Killed Haing Ngor.” This is my real-time and crowdsourced podcast in which we explore lingering questions about the murder - and the legacy of Dr. Haing S. Ngor. He was the actor who starred as Dith Pran in “The Killing Fields,” who went on to become a humanitarian and a businessman.

This is the second episode of a two-parter, in which I talk with journalist Jon Swain and photographer Roland Neveu. Along with Ngor, they share the distinction of having been the only people on the set of “The Killing Fields” who were also in Phnom Penh in 1975.

In the last episode, we looked at Dith Pran, who was of course the New York Times assistant reporter. In this episode, we look at Haing Ngor -- as the film was being made.

It was 1983 [Correction! I misstated this in the audio!] and “The Killing Fields” was being shot in Thailand. As someone who witnessed the immense tragedy of the fall of Phnom Penh, Jon Swain had doubts that Hollywood could do it justice.

He was dispatched to the set by his newspaper, The Sunday Times.

SWAIN: Any misgivings I had were taken away straight away because I was taken to a scene they were shooting in an old-fashioned historical building in Bangkok, which was being used as Preah Ket Melia Hospital in Phnom Penh. And it was a horrific scene at the time in 1975, in the fall of Phnom Penh: the hospital was full of wounded people - overflowing with wounded people - and the hospital staff had mostly left because of the dangers of rockets falling on Phnom Penh at that time, and they were frightened of the arrival of the Khmer Rouge. So it was brimming over with wounded civilians and soldiers. And the scene I saw in real life was a corridor full of wounded and dying people - with so much blood on the floor that it was actually being washed down the lift shaft by someone sweeping the corridor with a broom. And they recreated the scene very, very vividly in the film.

The scene was accurate – to the point of flashback.

SWAIN: The first thing I saw was this corridor, full of Thai extras lying motionless in the corridor covered in “Kensington gore” - make-believe blood – not moving for hours and hours and all of that. And it's just brought the whole horrific image back to my mind, and I felt that I - I was seeing reality, really.

Jon Swain, as I said, was the correspondent for the British newspaper, “The Sunday Times.” He’s played by Julian Sands in the film. Photographer Al Rockoff is played by John Malkovich. Sydney Schanberg - the New York Times correspondent - is played by Sam Waterston. And Dith Pran, as we know, was played by Haing Ngor.

The first time Jon met Ngor was on the film set. He was immediately impressed by his commitment.

SWAIN: He had a calmness and a depth to him, which was which was interesting. And it was only later on, as I got to know him, I learned bits and pieces of his background - he didn't talk about it. But thinking about it now, or thinking about it, even at the time - he was clearly still traumatized by the horrors he'd been through. And yet he was desperate to - because he was so he was so devoted to playing the role of Pran. It was real life for him. It was as if he was when he was playing, in a sense - with the emotion and everything - of what happened to him.

Roland Neveu, whom we also heard from last episode, is a photo-journalist. His war-zone work spans from Cambodia to Afghanistan, Lebanon, El Salvador, the Philippines, Uganda and Iraq, among other spots.

Roland has also worked extensively on film sets. IMDB lists 36 movies. Many of them are Indochina classics like “Platoon,” “Heaven and Earth,” “Good Morning, Vietnam,” “Born on the 4th of July,” and “City of Ghosts.”

That started as a lucky twist of fate. Columbia Pictures was the distributor of “The Killing Fields” in the US. Roland was based in Bangkok, Thailand, when Columbia found itself in need of an on-set photographer. So he got the call. Roland has sent me some fantastic photos from the set and some other moments in this episode , you’ll definitely want to look at on the webpage.

And as soon as he got on set, Roland became very popular.

MPN: And that’s where you met Haing Ngor?

NEVEU: I met Haing. Because basically when I got on the film, I was the only who had been in Phnom Penh at the time and who had witnessed the story. So in fact, it I became more sought-after by the actors and by the crew: “So you were there. Tell us.” You know - that kind of situation. Of course, Haing was - being an American-Asian, I would say more shy you know, than the other actors. You know, like Julian – Julian Sands. I really developed a very good relationship with Julian. We were always talking because Julian always wanted to know what happened, and he was playing John Swain which I knew a little also, so that was very interesting line of chit-chat on the set. And slowly Haing -we start to talk, and he start to tell me his story as well.

Reading “A Cambodian Odyssey,” Haing Ngor’s memoir, the treatment of Ngor by filmmakers struck me as somewhat manipulative. Obviously, I know I’m looking at this through the hindsight of a 2023 lens.

Still - Ngor was famously plucked from the Long Beach refugee community and cast in the film. He was then told by the director Roland Joffe to draw upon his personal tragedies to play Dith Pran.

But Ngor had never aspired to acting. He had never studied it. And in 1983, a man who’d survived massive traumas – including repeated torture and witnessing the deaths of both his wife and father, and who had never had any counseling -- was told to dive into method-acting.

I don’t think there was any malicious intent by the filmmakers in 1983. But my hunch is that - 40 years of evolution later - there’d be greater sensitivity to trauma now.

An article from the October 28, 1984 issue of The New York Times. Sounds like a PTSD-related flashback to me.

All that said, when it came to method-acting - Ngor not only rolled with it, he excelled at it. Roland says my concerns are misplaced. He’s been on a lot of sets. What matters is that the actor and director work in consensus, which is something Ngor and Joffe certainly did.

NEVEU: Oh, he was eager to do the most he could do. When you're when you're not in a movie business, and you know that you redo a scene like 10 times, 15 times - because the director ask you - so Haing never questioned that. He was totally eager to get the performance out of himself to tell the story. I mean, he was driven, in fact, to tell the story on the movie. And you can feel it … He was – 150 percent, really - all the time. That was interesting.

Method-acting, it turns out, was something Ngor could keep in perspective.

NEVEU: Yeah, very often, I hear him tell him, “It's okay. It was much, much worse in Cambodia.” He said, it never came to the level of difficulty that he experienced in the real life.

Ngor wasn’t the only one who was dedicated.

SWAIN: It was so it was so heartening, as someone who lived through that experience, to see the film crew – and, obviously the actors - but the film crew as well, be completely immersed in “The Killing Fields” story. And they were they were reading up on it at nighttime - stuff on Cambodia. And they felt it was a really, really important subject that they were dealing with.

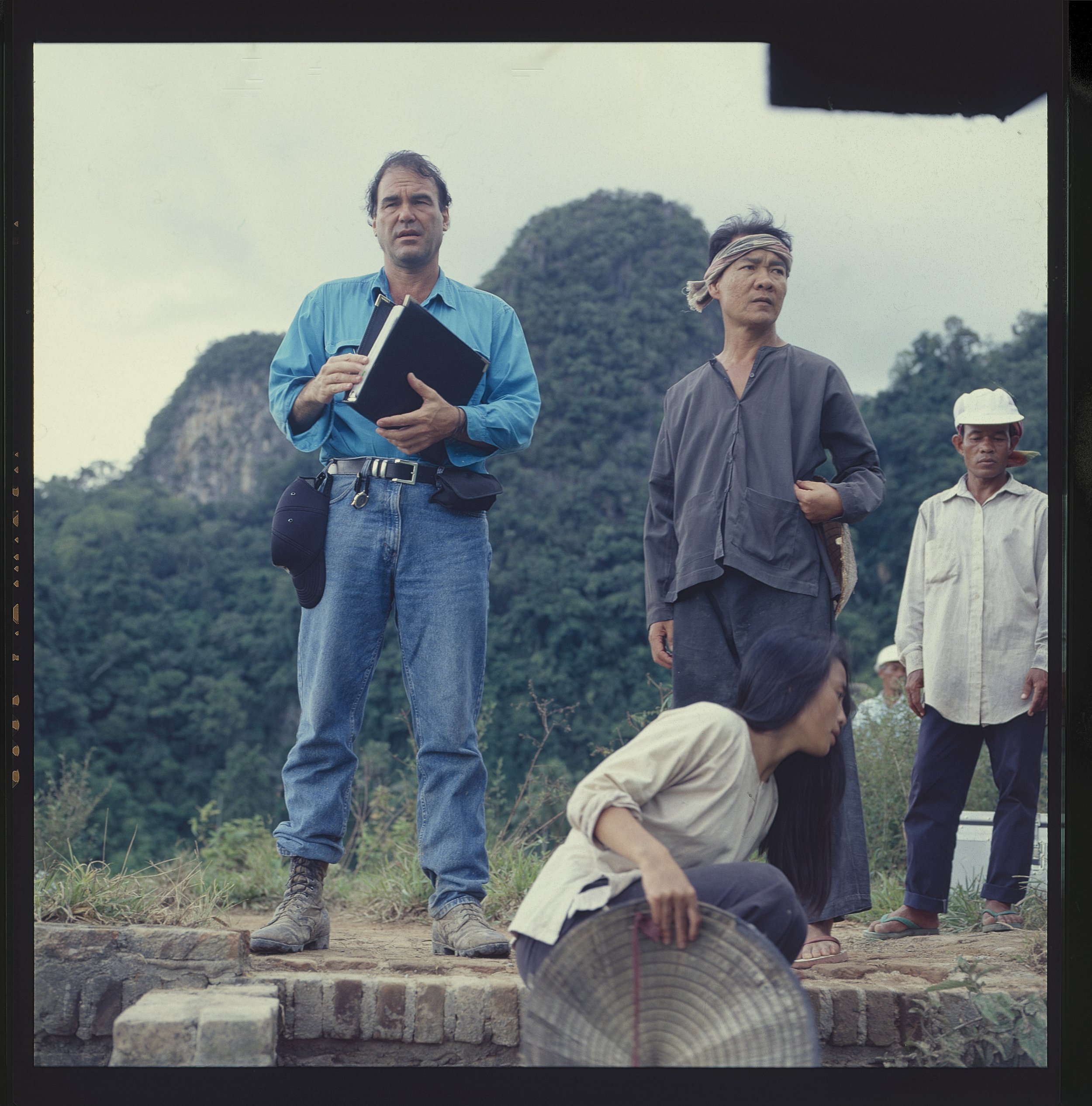

Photos courtesy of Roland Neveu. Director Oliver Stone with Haing Ngor on the set of “Heaven and Earth.” A portrait of Ngor taken on the set of “Heaven and Earth.”

Remember in the last episode, I stole a clip of Dith Pran speaking from an ABC News Prime Time Live broadcast? It’s a report by Diane Sawyer. It was 1989 and ABC News took Dith Pran and Haing Ngor back to Cambodia.

The Vietnamese military had occupied Cambodia since it forced the Khmer Rouge from power, in 1979. Ten years later, it was withdrawing. Cambodia had become a quagmire for Vietnam.

Roland happened to be in Phnom Penh at the same time. He was able to spend time with Ngor as he reconnected his previous life. The one where he was a doctor, engaged to his fiancé, and whose family had some successful businesses, like a lumberyard, and a trucking company.

NEVEU: And I think it was very happy to be able to, to retrace his steps during the Khmer Rouge and at the same rebuilt his Khmer-ness, his Cambodian-ness, understanding you know, trying to re assess himself. I walk with him around in Phnom Penh So we walked around there taking picture and people recognized him, you know, so it would stop all the time people and talk to people talk to him. So that was kind of interesting as well.

Roland ran into Ngor yet again. It was on the set of “Heaven and Earth.” That was an Oliver Stone movie about Vietnam released in 1993, in which Ngor had a role. He had grown from the man he was a decade earlier, when “The Killing Fields” was made.

NEVEU: When I saw him several times, on Heaven and Earth and in Cambodia – he was confident. He gives the impression that he was in control of himself, and he’s enjoying projects, he’s enjoying what he’s doing.

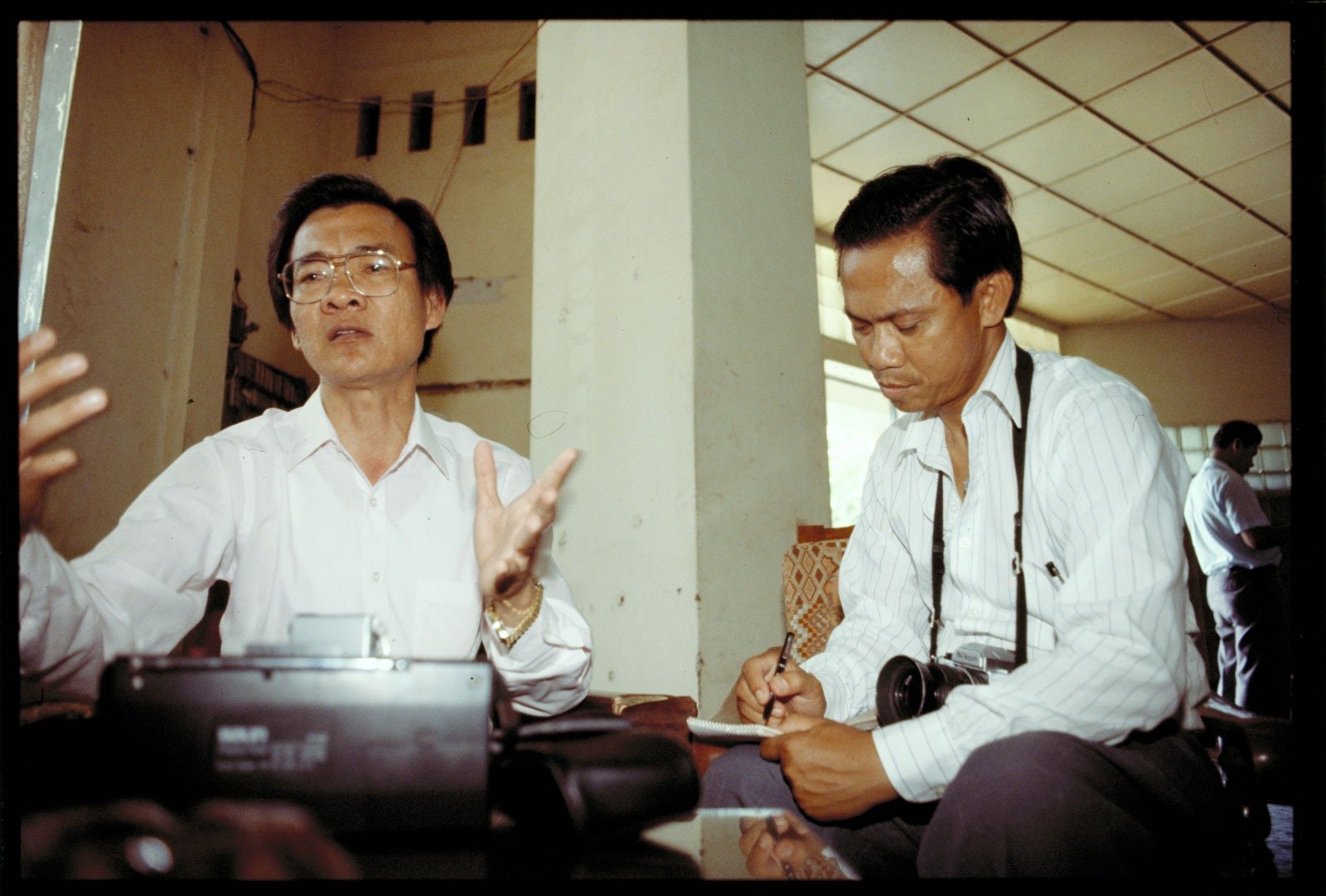

Photos courtesy of Roland Neveu. Haing Ngor and Dith Pran; Haing Ngor with monk near Phnom Bati, with whom he met when he returned to Cambodia in 1989; Haing Ngor - who would be recognized in Cambodia - chats with people on his return visit in 1989.

For all its intensity, “The Killing Fields,” of course, has a happy ending. After being forced from the French Embassy, Dith Pran spends years in forced labor camps, pretending to have been a peasant in his previous life, or at least working class.

He eventually escapes the Khmer Rouge, crossing the border into Thailand, to a refugee camp. There, he reunites with Schanberg.

Schanberg soon wrote, “The Death and Life of Dith Pran.” It’s a long-form article for the “New York Times’” Sunday magazine. It’s the story “The Killing Fields” is based on.

Haing Ngor, as we know, didn’t get his happy ending. Or, at least, the one he got was cut tragically short. He was murdered on February 25, 1996 – in the parking lot of his apartment building in Los Angeles. Police call it a botched robbery – although as I’ve said in the past, I’m not convinced.

Here’s Jon’s reaction to the news.

SWAIN: It was total disbelief. I mean, I thought, What a cruel irony is that a Cambodian who had suffered so much - imprisonment, lost his wife under the Khmer Rouge, suffered all those hardships and survived, got himself to America and in the country - which was his salvation in a way - he should be murdered a few years later. In America, where he’d settled. It was unbelievable. It was a complete cruelty, cruel irony for him.

“The Sunday Times” sent Jon to Los Angeles to investigate the possibility of the Khmer Rouge having killed Ngor – something neither he nor I think holds any water. Check out my perspective episodes 9 and 10 of this podcast, called “Finding Comrade Duch.”

Roland had a slightly different reaction to the murder.

NEVEU: I was absolutely surprised, in a way. But I lived in LA so I know - LA can be a very treacherous place. And when you hear okay, you guys get killed near his house. Okay, we are in Los Angeles, so it's not something which is going to surprise you.

What’s really amazing to Roland, Jon and me, is how well “The Killing Fields” has endured. The 1970’s are further and further away, but the movie hasn’t aged at all. It’s still on-point, it’s still tight – and nearly 40 years later, it’s still relevant.

SWAIN: yes - I'm extremely pleasantly surprised because everyone still talks about “The Killing Fields” when they talk about Cambodia - in England even, or in France - where it’s “La Déchirure.” And it's a seminal film - which has survived for many, many years. And it's you know, a journalist friend of mine was the other day in England - who covers war, and is in Ukraine at the moment - was asked to what her favorite war films were and one of them was “The Killing Fields.”

There’s a thought that took root in the back of my mind in the early 1990’s, when I was based in Phnom Penh.

The Paris Peace Agreement had been signed in 1991, to end Cambodia’s civil war. It wasn’t just Cambodia’s armed groups that signed it. There were four of those. Nineteen different countries signed it – all pledging to support a UN-supervised peace deal.

Think about it – officials from nineteen different countries got together, at various stages, to fix a country that - at this point - had little strategic significance. That includes the US, China, Vietnam and the Soviet Union – none of whom were all that cozy at the time.

This brings us to William Shawcross. He’s the author of, “Sideshow – Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia.” The book is another seminal work – and the title says it all.

MPN: I remember sitting in the Foreign Correspondents’ Club in Phnom Penh and William Shawcross gave a talk. And he credited “The Killing Fields” with actually helping launch the peace plan. That that, you know, the international community basically got off its derrière and was reminded of, you know, Cambodia was this awful situation, it was still, it was still a mess. Granted other things happened like the Berlin Wall had fallen and the world had shifted. But he really thought that the film pushed people to do all the nuts and bolts to get peace talks off the ground. Would you go that far?

SWAIN: Well, thinking about it. Yes, I would. I would share William’s thoughts on that. I hadn't thought of it before, but I think he would be right because it had did have that sort of such an impact. I t put Cambodia on the map, internationally and spurred that sort of feeling that the international community must do something.

I don’t know about you, but until that moment: I didn’t know a movie could do that.

After escaping Cambodia, Dith Pran settled in the United States, reuniting with his family. He became a photographer for The New York Times. He died of cancer in 2008, at the age of 65. Sydney Schanberg died in 2016. He was 82.

Al Rockoff remains a photographer, and lives in Florida. He still goes back to Cambodia from time to time. Roland Neveu remains a photographer and lives in Bangkok. Journalist Jon Swain lives in London.

We’ll wrap here. One last thing, a few weeks before Jon Swain and I spoke, actor Julian Sands who portrayed Swain in “The Killing Fields,” was confirmed to have died while hiking in the mountains outside Los Angeles. He had been missing for five months. I’ll put a clip of Jon’s thoughts on the webpage.

Jon was someone I first sought out for an interview for this podcast’s “Journos” trilogy – for his thoughts on how dangerous it was to work in Cambodia in the 1970’s. We didn’t connect in time for that. But I’ve put some other clips of his on the webpage in episode 12, “It’s Always the Fixer.”

Thank you for listening. My name is M.P. Nunan.

This is episode 13 – my baker’s dozen – and I will be taking a brief break from producing “Who Killed Haing Ngor” as I go traveling. I guess I’ll call what I’ve done so far, “Season One.” Look for more in late September or early October. Remember, this is a crowd-sourced podcast – an experiment in journalism.

If you knew Haing Ngor personally and would like to contribute – even just an interesting anecdote - please get in touch. If you know any details about his murder you think are relevant, please get in touch. I’ll still be paying attention, even while I’m traveling. The best way to reach me is to email whokilledhaingngor@gmail.com

Haing is Ha I ng. Ngor is N G or

See you n Season Two.