Journos

I can count on one hand the best international journalism movies ever made. There’s “Salvador,” “The Year of Living Dangerously,” the relatively recent, “Balibo,” about East Timor; and of course, “The Killing Fields,” around which this podcast revolves.

Don’t throw “All the President’s Men” at me; that’s domestic. These are international journo movies. And - when referring to members of our own tribe, we often just say “journo.”

Welcome – this is episode 4 of “Who Killed Haing Ngor,” a real-time and crowdsourced podcast in which we explore both lingering questions about the murder and issues connected to the legacy of the Dr. Haing S. Ngor, the actor from the “Killing Fields” who went on to become a political activist and a businessman.

“The Killing Fields” takes some creative license in its retelling of some characters’ actions amid the fall of Phnom Penh in 1975. But it makes clear how confusing and dangerous it is to work in a war-zone, especially with a guerilla army as insane as the Khmer Rouge. It also shows how at times local journalists, the fixers, who work as interpreters and producers for the international press corps, get screwed over. Privileged foreigners usually get to leave a crisis zone that’s not their home, while members of the local press have to stay. The issue of fixers deserves an episode itself, and I hope to get to it.

At the moment I’m looking at the international press who covered Cambodia in the 1970’s. I could produce an entire extended podcast series on just them.

· There’s photographer Al Rockoff, a US Army vet, who not only featured in “The Killing Fields,” but who famously once died on the battlefield in Cambodia for several minutes before doctors brought him back to life.

· There’s Kate Webb, the Bureau Chief for UPI, who was reported dead after she and a few other journalists were taken captive by North Vietnamese troops in Cambodia. Weeks later they were released, and Webb enjoyed the rare privilege of reading her own obituary.

· There’s Elizabeth Becker, one of three journalists invited to meet Pol Pot in 1978, while the Khmer Rouge were in power, and one of just two to make it out alive.

There’s Neil Davis, Horst Faas, Philip Jones Griffiths – the list goes on.

But there’s no story - no mystery, really - more enduring than the disappearance of Sean Flynn and Dana Stone, and the decades-long quest by photographer Tim Page to resolve their fate.

This story is so topsy-turvy I’m breaking it into three episodes. The first will set the scene, and the second will dive into more of the mystery surrounding Flynn and Stone, with its dead-ends and false trails, mutineers and adventurers that captivates people like the disappearance of Amelia Earhart.

Here’s part one.

HARRIS: “Tim fortunately has kept everything you know, so he has the missing journalist booklet, he's got notes saying, you know, “Do not go out without telling people where you go” and yeah, he's just hung on to absolutely everything. Plus, you know, I've been doing research for the last 20 years, basically - since Tim moved here with all his stuff on tracking down what happened to these these guys.

That’s Marianne Harris, known as “Mau.” She’s the long-time partner of Tim Page, the photographer who died in 2022 at the age of 78. Tim is an absolute legend in Cambodia and Vietnam press corps circles, a British photographer known for his frontline photos, wild parties, stoner habits - and his search for Flynn and Stone. I’ll post some links and the best obits for Tim on the Who Killed Haing Ngor webpage.

Harris is a journalist in her own right, and is now working on a two documentary projects. One is about Tim’s search for Flynn and Stone, called “Closer to the Sun.” Another, “Vanished,” is an homage to the 42 international press who were killed or went missing in Cambodia between 1970 and 1975. That’s not counting Khmer journalists.

The same way “gonzo” is a term that follows around Tim Page, “swashbuckling” is the term that follows around Sean Flynn. It’s a hand-me-down from his father, the legendary, old-time Hollywood actor, Errol Flynn. But - there’s nothing like being a war-photographer to set yourself apart from your movie-star dad.

If you look at “The New York Times’” marvelous online archive, Times Machine, at 1970’s Cambodia coverage, you’ll see headlines like, “Newsmen Lead Perilous Existence in Cambodia.”

We’ll let slide the casual sexism of the era. That story from June 7, 1970 details the deaths and disappearances of 23 journalists, including 8 who disappeared in a single incident – later updated to nine. It includes this paragraph: It includes these two paragraphs.

Compared to Cambodia, covering the war in Vietnam is like touring with American Express. Instead of traveling down lonely roads in rented cars, as they do in Cambodia, war correspondents in Vietnam are taken to the scene of the action by planes and helicopters and put down only where there are friendly troops.

Correspondents in Vietnam take chances, but only those taken also by the troops. In Cambodia, journalists have rushed in where soldiers often have feared to tread.

That’s an enormous insult to the Vietnam press corps, who risked their lives plenty. After all, where there are troops, there are live-fire situations.

But it also speaks to Cambodia’s “Sideshow” status. The entire nation was collateral damage to the Vietnam War, and so was its under-resourced and under-recognized press corps – both Khmer and foreign.

OBAMA: And those who make the mistake of harming Americans will learn that we will not forget, and that our reach is long, and that justice will be served.

In July 2014, there were five American journalists and aid-workers held captive by ISIS in Syria. President Obama launched a secret mission – sending the Army’s Delta Force and Navy Seal Team Six to rescue them. A firefight with militants took place, but the hostages had previously been moved to a different location. Within weeks, journalists James Foley –known as Jim -- and Steven Sotloff were executed on camera.

OBAMA: Today the entire world is appalled by the brutal murder of Jim Foley by the terrorist group ISIL. Jim was a journalist, a son, a brother and a friend. He reported from difficult and dangerous places, bearing witness to the lives of people a world away.

There is absolutely no merit to comparing tragedies; they are all equally appalling.

But we are simply much more aware of these tragedies today - far more than the public was 50 years ago. The Cambodia press corps’ extraordinary casualty rate is what Mau Harris wants to highlight in “Vanished.”

CLIP: HARRIS: It's actually a tribute to the 42 missing. So it's telling their story, because yeah – [if] 42 missing journalist happened today, there would be an uproar. And the fact that the only people that remember these 42 are their family and friends. And so what we wanted to do was an homage to them.

This is the scene, Sean Flynn, Dana Stone and the entire press corps found themselves in.

It’s early 1970. Flynn worked for Time Magazine, while Stone was a freelance cameraman on assignment for CBS.

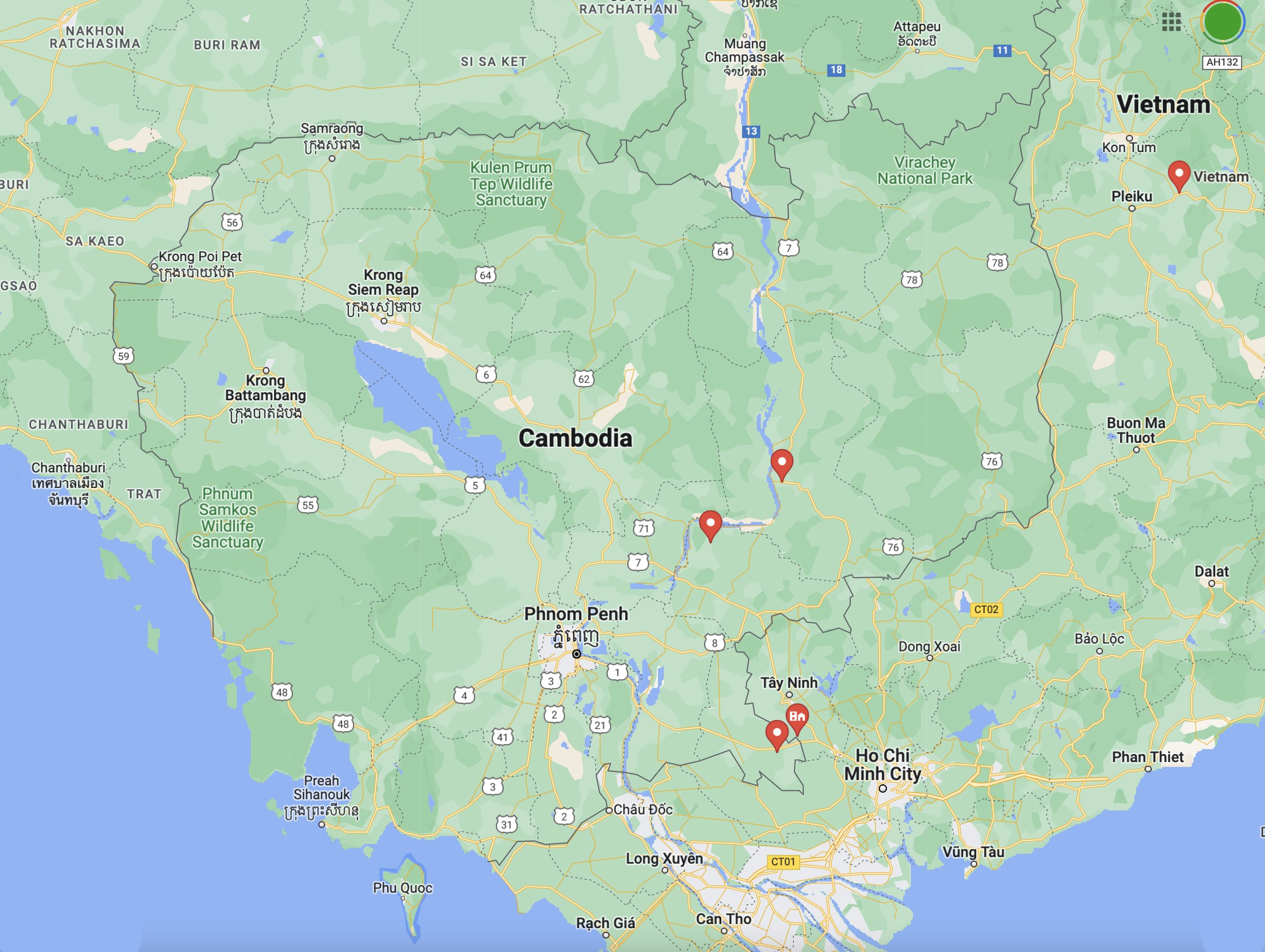

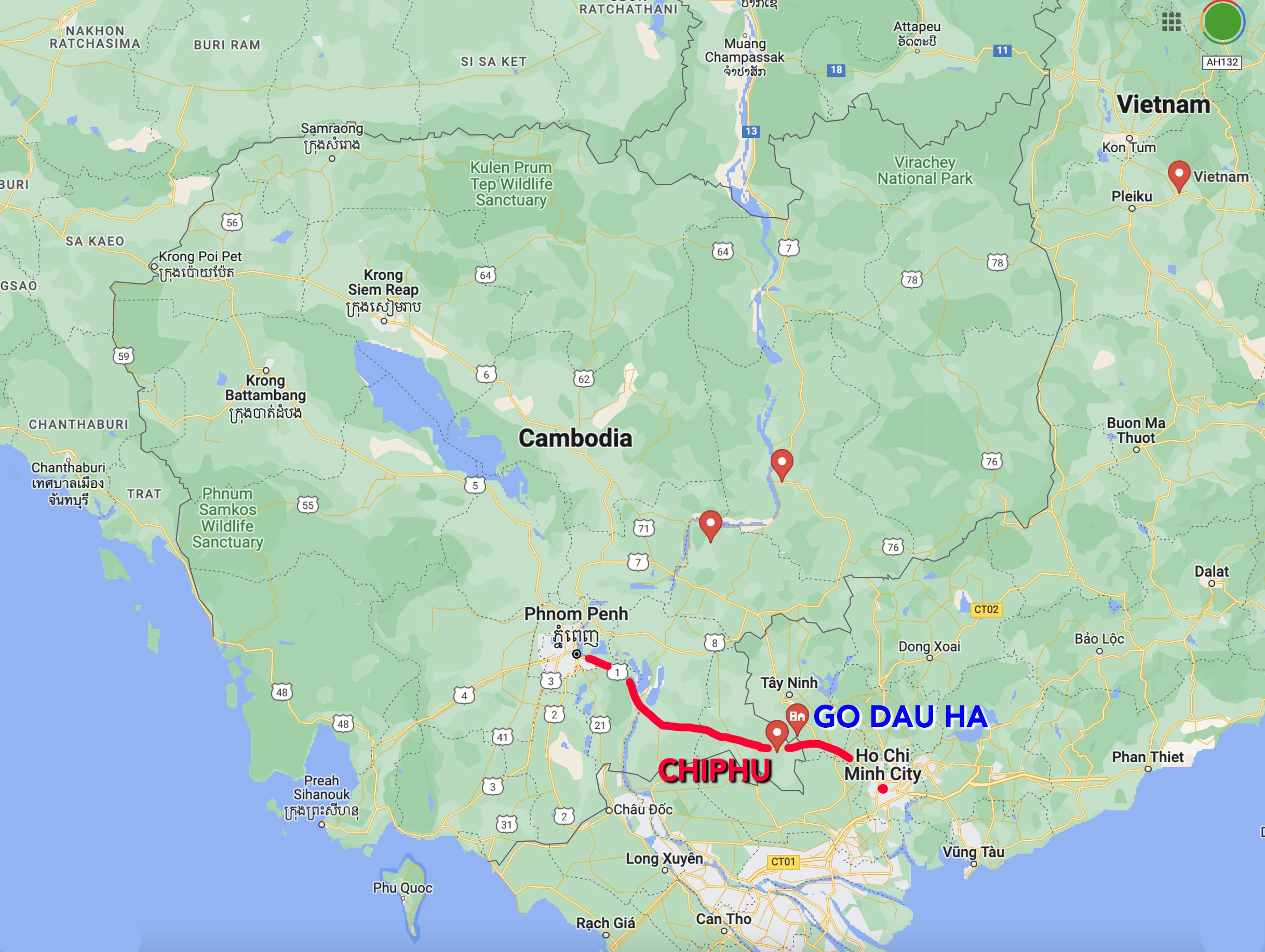

The US war in Vietnam is not going according to plan, while in Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge are just beginning to gain steam. Route One, which links Cambodia’s capital Phnom Penh to Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam, is probably the most dangerous in the region.

The US had been secretly bombing the Cambodian countryside, looking to destroy North Vietnamese supply lines – the Ho Chi Minh Trail - since 1969.

This is significant – out in Cambodia’s provinces, there were not only Khmer Rouge fighters, but also Viet Cong guerillas and sometimes North Vietnamese troops. Journalists never knew who they were going to run into.

If US forces were illegally straying into Cambodian territory? That’s a huge story.

This is before GPS. Out in the field, journalists couldn’t determine if jets streaking across the sky at a distance, were on this side of that side of the border.

Here’s Mau Harris. The reporter whose name she can’t think of right away is Burt Fields.

HARRIS: Sean had gone out with -- he just died recently. I can't think of his name at the moment -- and saw American planes flying over Cambodia and saw VC and North Vietnamese troops on the ground. But there was no frame of reference to you know, those planes could have been anywhere those troops could have been anywhere.

That’s exactly the kind of story Tim Page might have chased up. But Tim had been wounded in Vietnam and was medevacked to the US - where he spent several months recuperating. There are photos of Flynn actually carrying his stretcher – and I’ll post links to those the webpage. That was the last time Page and Flynn would ever see each other. CORRECTION: I misidentified this photograph in my on-air script. It was not the last tine Tim Page and Sean Flynn saw each other. That photo’s from 1966, and another time that Tim was wounded. Sean Flynn visited Tim in the hospital before he was medevacked out, when he was wounded in 1969, but Tim couldn’t see him because his eyes were bandaged. Sean gave Tim a tiny Buddha amulet, which Tim kept for the rest of his life, and even held it was he died. My thanks to Mau Harris for pointing that out.

Photos of Tim Page after being wounded in 1969, taken by John Fairbanks, a US Public Information Officer. After seeing the documentary, “Unseen War,” he sent the photos to Tim, along with a note: “I took those photos of you on the chopper and I was told that you didn’t make it !!”

Photos courtesy of Marianne Harris.

Flynn took some time off and did some traveling, before deciding he had one more story in him. And if the US was invading Cambodia, it’d be a big one.

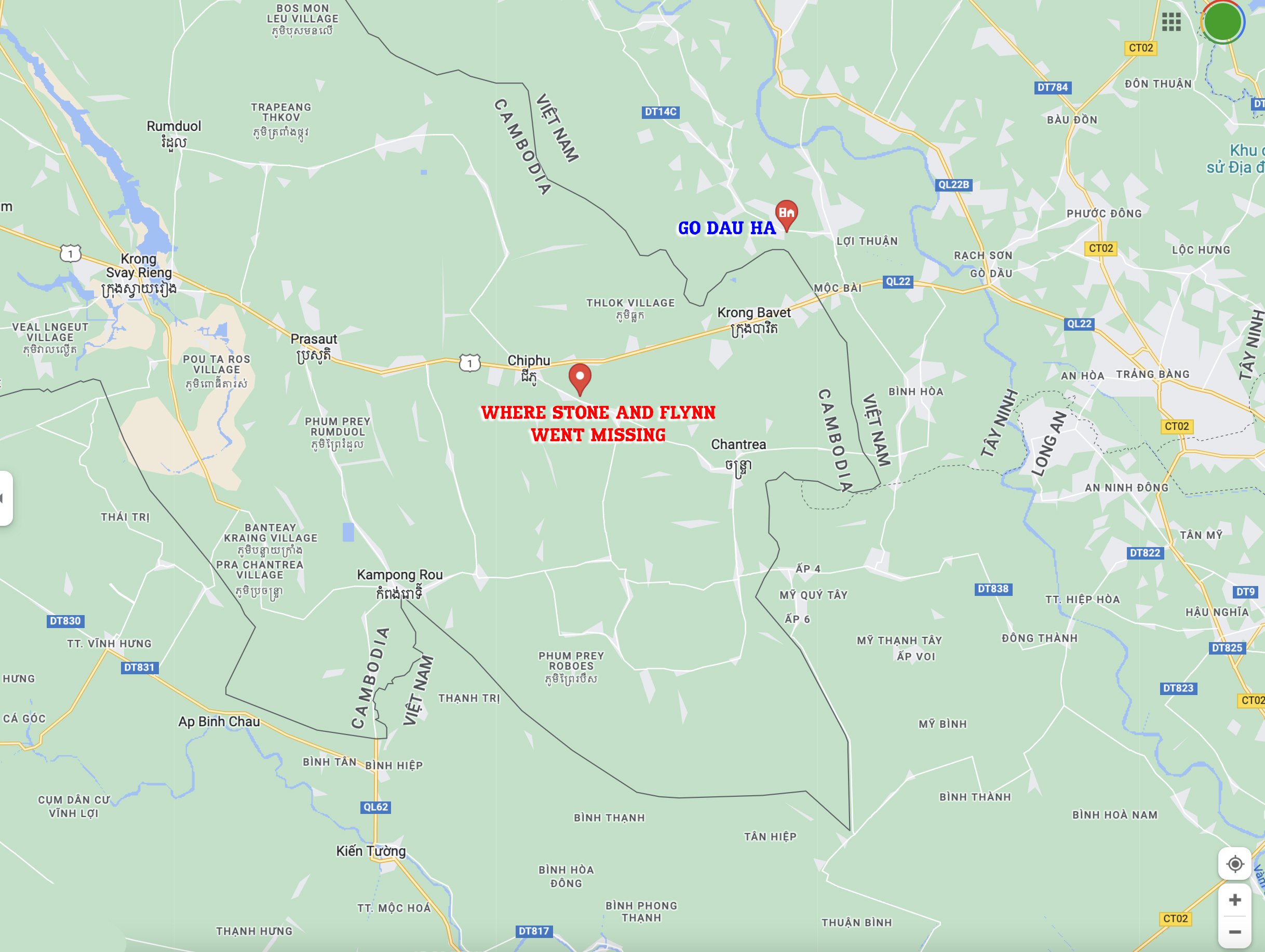

A few days after his trip with Fields, Flynn teams up with Dana Stone to go out on the story again. They had competition. A Cambodian general, keen on showing that Cambodia was in charge of its own territory, organized a press junket down Route One toward the border, to a town called Chiphu. I’m putting a map up of all this on the webpage. (Go Dau Hau, the Vietnamese border town will be relevant in Journos II.)

Flynn and Stone took off on their own, on motorcycles, a day earlier. Quite possibly, they wanted the scoop before the whole press corps got it, or different images than what the junket would prompt.

HARRIS: Their intention was to carry along Route One, photograph all of this that was happening, and go back to Saigon that way.

The press junket was a disaster for the general: Chiphu was destroyed, suggesting that - despite official claims - Cambodia’s sovereignty was repeatedly violated.

Oddly enough, despite having gone out into the field earlier, Flynn and Stone joined the press junket down in Chiphu. Everybody saw them. But instead of going back to Phnom Penh to file that story – the same one everyone got – they made a different decision.

They had seen an abandoned car – one that belonged to missing journalists. Colleagues from the Phnom Penh press corps. Maybe…. This merits some investigation.

Clearly, it was dangerous. They faced a decision that probably every journalist in a conflict zone has confronted at some time or another: Do we go down that road or not?

HARRIS: So there was a car with Claude Arpin and four Japanese journalists that had been shot up and was parked across the road. And they were gone. The journalists were gone. So Sean and Dana went down to see what happened. And they were captured.

Thank you for listening. Part II of “Journos” will be posted soon.

My name is M.P. Nunan. Remember, this is a crowd-sourced podcast – an experiment in journalism.

If you knew Haing Ngor personally and would like to contribute – even just an interesting anecdote - please get in touch. If you know any details about his murder you think are relevant, please get in touch. The best way to reach me is to email whokilledhaingngor@gmail.com

Haing is Ha I ng

Ngor is N G or