The Oscar Winner vs the Orphanage

What happens when the international community takes a country that’s been shut down by war for two decades, throws together a peace plan and a new government, and suddenly opens that country up to the world?

Two things. First: foreign investors flood in. They want to take advantage of an untapped market. That creates a capitalist “Wild West” that the new government’s regulatory bodies can barely keep up with. And that’s putting it kindly.

Two, it creates a “compassion fad.” Scores of international aid agencies and non-governmental organizations rush in to help the under-served Cambodian people with a vast number of programs and projects. Some are more professional than others. And that’s putting it kindly.

Welcome. This is Episode 7 of “Who Killed Haing Ngor,” a real-time and crowdsourced podcast in which we explore both lingering questions about the murder and issues connected to the legacy of the Dr. Haing S. Ngor, the actor from the “Killing Fields” who went on to become a political activist and a businessman.

This is the scene Haing Ngor found himself in in the 1990’s. He was an ex-patriate Cambodian who came home to invest – hoping to both make money while helping rebuild a war-ravaged economy. He also launched the Haing Ngor Foundation to pursue humanitarian work.

On top of that, back in Los Angeles, he was shopping a screenplay – about a little-known problem within the international refugee system, that still resonates today.

CASELLA: What I can say is that he didn't act like a movie star if you could, you know, a quote-unquote movie star - if you could imagine what that would be like.

This is Emilia Casella. She was a journalist in Cambodia back in the 1990’s and – full disclosure – she’s also an old friend of mine. These are her impressions of meeting Haing Ngor.

CASELLA: He did not certainly seem flashy. He wasn't dressed expensively or he didn't have expensive, you know, jewelry. He didn't seem like someone who was trying to give an impression of being rich, or being important. He was quite an approachable. He was very willing to meet me and I think get his side of the story out, in terms of explaining why he was asking an orphanage to move from his property.

Emilia had come across a story: the Oscar-winning Haing Ngor was in a dispute with a Canadian national hero – Naomi Bronstein, who ran an orphanage in Phnom Penh.

Emilia’s Canadian and reported on this for Southarn Newspaper chain. That doesn’t exist anymore, but at the time, it consisted of around 50 newspapers across Canada.

The property was a villa – like any number of homes and office spaces in Phnom Penh. Haing Ngor bought it from Cambodia’s Forestry Department, spending $92 thousand dollars in 1991.

The property came with a pre-existing tenant – the orphanage that Bronstein ran, called Canada House. Three months before the lease was up in February 1993, Ngor gave Bronstein notice that her facility would have to move.

Bronstein asked for a six month extension, to which Ngor said no. When the lease was up - Bronstein refused to leave.

CASELLA: She was a hero, a controversial character as well. She was a one-woman band, so to speak, running this orphanage in Cambodia called Canada House, but she had started actually earlier than that, I think working in Vietnam.

In fact, Bronstein, who died in 2010, was a Canadian national hero. She won the Order of Canada award for her work with orphans in Vietnam, Cambodia, Korea and Guatemala.

There’s an important detail here: Bronstein named the orphanage Canada House, and put a flag up on the gate. But the facility had no official connection to the Canadian government. That will be important later.

Bronstein’s career was also marked by tragedy. Her grief-stricken expression was splashed across the front page of the New York Times in early April 1975. She was involved with “Operation Babylift,” an effort to evacuate orphans out of Saigon, launched weeks before its fall to North Vietnam. But that first flight crashed shortly after take-off, killing 138 people – many of them orphans. I’ll put that photo and some links up on the webpage.

The tragedy did nothing to shake Bronstein’s commitment to her purpose.

CASELLA: And so [she] was quite well known as this feisty person who would against all odds, do whatever she could to save children. And if that meant, maybe not following all the rules, or not following all of the the norms of normal humanitarian or development organizations, she sort of said, “Well, that's fine. My ultimate goal is to save children.”

But Haing Ngor was also a passionate man.

CASELLA: And he said, you know, “She's a Canadian. I'm a Cambodian. Please give me a chance to help Cambodians. I'm here to take care of my own people.” And he felt very much like he should - you know, that he wanted obviously to have the chance to do that. And that his foundation itself was not able to do everything it could because he had spent I think some of that money that he intended on a property that he then couldn't use.

Ngor took a step back from the orphanage controversy that began in 1993, leaving it to the Cambodia’ Ministry of Social Action - the body that governs such facilities - to sort out.

Emilia met Ngor again in 1995 – they actually ran into each other by chance. The orphanage dispute was still unresolved. But that’s not what they talked about.

CASELLA: He was very animated about it and said, I've got this. I've got this script and he gave it to me. So I didn't ask him for it, certainly he kind of offered it said, “Would you like to read it?” And I said, “Thanks. Sure.” And I did.

Emilia did what old friends do, for their podcasting buddies. She went out and dug through her storage unit and tried to find the script for me. She couldn’t find it.

CASELLA: I do remember that it was called “The Man From Year Zero.” And it was drama all around the concept of a Cambodian who had gone to North America, resettled - and then runs into his Khmer Rouge tormentor in his new country.

When the Khmer Rouge took over Cambodia, they believed their revolution was so historic that it reset the clock. So they changed the date to Year Zero – that’s where that reference comes from. “The Man From Year Zero” would be a war criminal from the Khmer Rouge.

Haing Ngor was going to play the bad guy – the KR thug. He was also ahead of the curve on a much bigger issue.

MCLAUGHLIN: So CJA was founded about 25 years ago, and was actually founded by a mental health professional. So he was working with victims and survivors of torture.

This is Daniel McLaughlin. He’s a Senior Staff Attorney at the Center for Justice and Accountability - CJA - in San Francisco. Again - full disclosure - I do the occasional freelance assignment for CJA.

CLIP: MCLAUGHLIN: And one of his patients actually ran into and saw the person who had tortured him - in the US. So this is somebody I believe he was from Bosnia. And he had moved to the US, but ran into the person who was responsible for his torture.

CJA has had a number of intriguing war-crimes cases in the US. One was a Liberian individual. One was Gotabaya Rajapakse, who’d become Sri Lanka’s President. And again, I’ll put some links up on the webpage.

Of course, the US Justice Department and the Department of Homeland Security, through ICE, investigate alleged war-criminals in the US. They usually deport them, often on immigration grounds. Unlike CJA, they don’t try them for alleged atrocities in US courts.

Certainly, the vast, vast majority of refugees in the US are ordinary people who have survived wars and other conflict.

McLaughlin doesn’t know of any prosecutions of Khmer Rouge officials inside the US. I couldn’t find any record of any, at least not on the Justice Department or ICE webpages.

Interesting to me, though is that the time Haing Ngor was working on the screenplay he showed to Emilia - 1995 – was just a few years ahead of CJA’s founding in 1998. Ngor had worked as a counselor to refugees arriving in Los Angeles. We can only guess now, of course, but I wonder if Ngor was aware of some former Khmer Rouge who had slipped through the cracks and into LA.

MCLAUGHLIN: You know, there's large Cambodian American communities and places like Long Beach, or Lowell, Massachusetts, sort of these“epicenters.” And so, the odds are that there are probably folks within those communities, you know, who played some role in the Khmer Rouge.

Despite the ongoing dispute with the orphanage, Haing Ngor did the best he could with his foundation. As Emilia remembers, In partnership with other organizations, he built schools in Takeo and Kandal provinces. He contributed to the building of five kilometers of road.

In one of those projects, Emilia’s not sure, but it was probably the schools, Haing Ngor teamed up with Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen. We’ll hear more about Hun Sen in the next episode.

Meanwhile controversy continued to swirl Canada House. In early 1994, Naomi Bronstein had become ill, and went home to Canada for treatment.

Even before that, Emilia had some concerns.

MPN: What did you see that made you a little concerned that it wasn't up to standard?

CASELLA: I mean, I saw kids with dirty diapers or no diapers, but you know, clearly I mean, they were they were certainly - you know, washing the kids down, you know. I mean it's not that they were being neglected by the staff. The staff were really doing their utmost you know, their best to, to, to feed the children and give the children - you know, the children were able to play around, they were playing in the yard, they were kind of running around and stuff. So it was not it wasn't a prison or anything like that. But but I felt that the kids really did not look like they were in good shape. And some of the younger ones looked really ill - like they needed medical attention.

With its director on the other side of the world, the orphanage was broke – it had no funding. Bronstein was not paying her staff, who had no budget for food or other necessities. The staff subsidized the kids out of their own pockets.

Bronstein did manage to send a little money from Canada from time to time. She had all sorts of plans for large-scale funding – she spoke about those with other Canadian reporters. I’ll post a link on the webpage. But they didn’t come together.

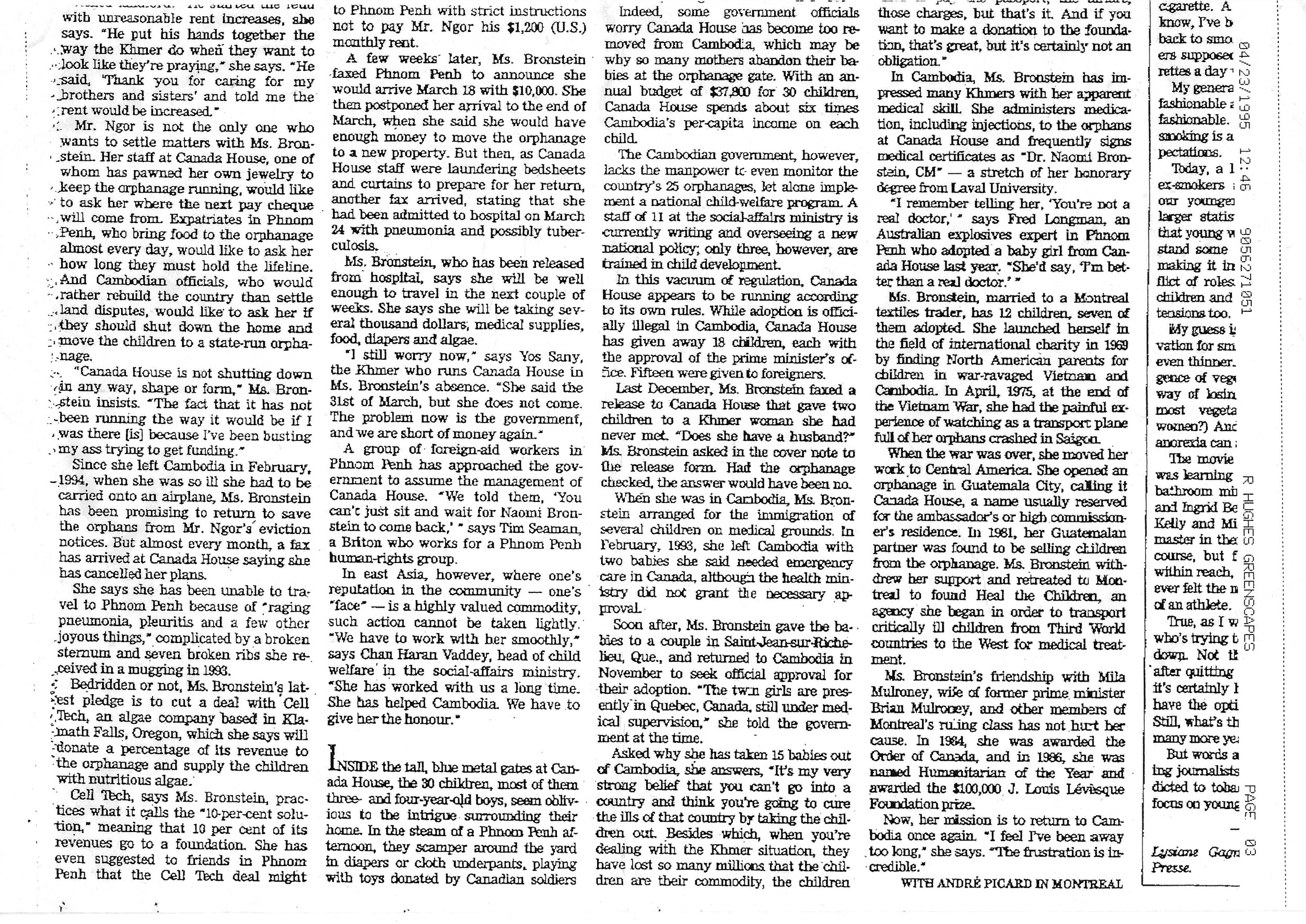

Copy of Globe and Mail story, courtesy of Emilia Casella. It’s an old fax of her competitor’s story in The Globe and Mail. Funding plans in these stories.

Remember, Bronstein had named the orphanage Canada House, but it had no official affiliation with the Canadian government.

Word of the orphanage situation got around. Soon, members of the international aid and diplomatic communities took it upon themselves to support it. An ex-pat bar held a fundraiser. Canadian peacekeepers with the United Nations pitched in to help.

CASELLA: It still felt like it was hanging on by its fingernails, as an organization. And that it was not really being run the way you’d expect an orphanage to be run.

Eventually, a team of ex-patriates, some of whom had adopted children from Canada House, got serious. They found homes for the kids in need. Working with the Cambodian government, they organized the merger of Canada House with another children’s facility – effectively shutting it down.

At some point during all of this, Bronstein had quit paying her rent. Emilia doesn’t know the exact dates. Maybe it was when the dispute started in 1993, or when she went back to Canada in 1994. But that means for a year or possibly two, Haing Ngor didn’t have a tenant - he had a squatter.

But that means for a year or possibly two, Haing Ngor didn’t have a tenant - he had a squatter.

CASELLA: So he got himself a little bit into a conundrum or a pickle when he ended up purchasing a property that he couldn't use. He didn't have lots and lots of money for his own foundation, at least I don't know because I never saw the books of his foundation, but it's not that he had a particularly large amount of money f or his own foundation either. And he said he really couldn't afford to rent another property when he had paid for the the property that he had expected to be able to use. So he was he was quite concerned about that.

One thing I want to point out: In Phnom Penh at the time, it would not have been difficult for someone of Ngor’s prominence to get police to carry out an eviction order – even of sick and destitute children. It’s easy to imagine other property owners doing exactly that – evicting orphans, without a second thought. That kind of thing was just par for the course.

With Canada House, that never happened. Maybe Ngor was a decent guy. Maybe he was protecting his reputation. Maybe it was a little of both. Instead, Haing Ngor white-knuckled it through his own financial problems.

I’ll let Emilia have the last word.

CASELLA: And he really felt that it was his duty to return to Cambodia and give something back to the country. He spoke quite passionately about that. And he said that, you know, Khmers who are in Canada, Khmers who are in in the United States, “We are the lucky ones - and we shouldn't feel guilty, but we should go back and help, or do something to help Cambodians who are in Cambodia.” And I think he did have guilt. He talked about this sort of sense that people might feel guilty because they had survived. And he wanted people to feel that they had a role in rebuilding their country. And he was also quite strong in saying that he wasn't doing this from any political aspirations - that he really felt that it was his duty as someone who was successful and lucky to come back to the country and contribute to the lives of people who were still in the country.

Thank you for listening. Before I wrap, there’s another tragic element to this story.

At some point, Haing Ngor gave his screenplay, “The Man From Year Zero,” to another journalist. Also Canadian. His name was Dave Walker. Walker was working with Ngor to develop the script, when Ngor was murdered in February 1996.

Years later, in 2012, Walker wrote about his sense of on-going loss about Ngor’s murder in The Phnom Penh Post. What’s interesting to me is that Walker says that - a month before he died - Haing Ngor told him he was planning a political run in Cambodia.

Two years later, on February 14, 2014, Dave Walker disappeared from the guest house where he lived in Siem Reap, Cambodia. Weeks later, he was found murdered. Friends attribute the murder to Walker’s desire to find former Khmer Rouge – a passion lit up by that screenplay, “The Man From Year Zero.” Others dispute that.

I’ve heard rumors over the years that Walker was pursuing stories about illegal logging, and for that he was silenced. But I’ve never looked into it myself.

Links are on the webpage. To this day, the murder of Dave Walker remains unsolved.

Thank you for listening. My name is M.P. Nunan. Remember, this is a crowd-sourced podcast – an experiment in journalism.

If you knew Haing Ngor personally and would like to contribute – even just an interesting anecdote - please get in touch. If you know any details about the murder you think are relevant, please get in touch. The best way to reach me is to email whokilledhaingngor@gmail.com. Thank you very much.