Finding Comrade Duch

When it comes to the murkiness surrounding the murder of Haing Ngor, there’s one person responsible for the most prevalent conspiracy theory. It’s Kaing Guek Eav, better known as Comrade Duch.

Duch was the head of Tuol Sleng, also known as S-21. That’s the Khmer Rouge prison and torture center, set up to “process” the so-called enemies of the revolution.

Duch was also the Khmer Rouge official whose case opened Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge tribunal in 2009. That’s where he said that Pol Pot, the Khmer Rouge top leader, had ordered the murder of Haing Ngor, 13 years before. In so doing, he resurrected a conspiracy theory that emerged at the time of the killing.

I don’t buy that line. And neither does Nic Dunlop, the Irish photographer who found Comrade Duch in a remote part of western Cambodia in 1999.

Welcome to “Who Killed Haing Ngor.” “This is the first of a two-part story – episodes 9 and 10 of that I’m calling “Finding Comrade Duch.” This is my real-time and crowdsourced podcast in which we explore both lingering questions about the murder and issues connected to the legacy of the Dr. Haing S. Ngor, the actor from the “Killing Fields” who went on to become a political activist and a businessman.

Nic Dunlop is the guy who literally “wrote the book” on Comrade Duch – and how he became fascinated by him. His book, “The Lost Executioner” is more than just an adventure tale. It’s a very thoughtful chronicle of Nic’s relationship to Duch’s story, Cambodia’s story - and the shades of grey between evil and the moral high ground.

And once again – full disclosure – Nic Dunlop is a friend of mine.

For anyone who’s ever gone to Cambodia’s capital Phnom Penh, the chance to visit Tuol Sleng and the “killing fields” at nearby Choueng Ek has probably been thrust at them – by tour guides, hotel staff, or taxi drivers. They’re among Cambodia’s most famous tourist sites.

Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge past is both incredibly recent and incredibly compelling. It’s like visiting Auschwitz, the Nazi concentration camp, while in Poland. Tuol Sleng’s a museum now, and people go to try to get a sense of the sheer horror of the Khmer Rouge period.

NIC: My name is Nic Dunlop. I'm a photographer and I'm author of “The Last Executioner,” the biography of Pol Pot’s chief executioner Comrade Duch.

Nic was one of those visitors to Tuol Sleng in 1989, when he was just 19.

The Khmer Rouge were meticulous record-keepers – photographing all in-coming prisoners. Now, thousands of those mugshots are on display. They’re a makeshift memorial to the dead. Those displays are punctuated by a few shots of the Khmer Rouge hierarchy, including Comrade Duch.

NIC: I remember very clearly the first time of going into Tuol Sleng, at the age of - I think was 19 at the time. And you know, amongst the photographs of all the victims and the thousands of mugshots of the youths that we've all seen that have come to represent the Khmer Rouge revolution, were a few photographs of the people around the prison. And they seem to me to be the most terrifying people. And of course, there was that photograph of Comrade Duch. And that was the photograph that I later carried with me to different parts of Cambodia.

Somewhere between 12 and 20 thousand people passed through Tuol Sleng. Many of them were Khmer Rouge - accused of having betrayed the revolution.

Duch and his fellow interrogators – or torturers - told prisoners that if they told the truth, their lives might be spared. Many confessed to crimes they didn’t commit. Tuol Sleng has copies of some written confessions that are long, earnest -- and desperate-sounding.

That their lives would be spared was of course a lie: the known survivors of Tuol Sleng number in the single digits.

MPN: Why did the Khmer Rouge turn on its own people so frequently?

NIC: I think that the whole purpose of these purges was to a constant process of revolution of purging, of cleansing, of ridding the ranks of enemies, and they were deeply secretive and very, very paranoid. And they were convinced that their revolution was unique, that it was the most far reaching and radical revolution the world had ever seen. And they believed that it was the envy of suddenly the communist world . And they were paranoid about the Vietnamese for instance, undermining that revolution.

Nic mentioned a photograph. On that first visit to Tuol Sleng, he snapped a photo of the Comrade Duch shot. And he kept it in his camera bag – for years.

NIC: I just took a photograph of the photograph and I carried it with me and I remember very clearly asking several colleagues and friends; you know when the Khmer Rouge began to look like it was really on its last legs as a movement, you remember there were thousands of defectors almost on a weekly basis. And I thought, Well, look, the likelihood of him still being alive is probably quite remote.… you know, I thought he probably would have been a victim of one of the many purges. But I thought, Wouldn't it be an interesting feature to go to travel, traverse these former Khmer Rouge zones and talk to people try and , go on pursuit in pursuit of this guy and try and find out what happened to him.

Nic was so captivated by his Cambodia visit that he dropped out of art school and to try to make it as a photographer.

But let’s back up for a minute. What made an Irish teenager interested in Cambodia in the first place? Listeners probably won’t be surprised to hear - it was “The Killing Fields.”

When Nic was 15, he moved with his family from Dublin to London. He wasn’t pleased about it. It was 1984 – the same year, “The Killing Fields” came out.

NIC: There was a flurry of films about the war in Vietnam at that time, but this is the film that - to me - tried to tell a very complicated story, and did it in such a way that it was it was a kind of a beautiful vision of hell. And I think it's that tension between you know, a really powerful story, very well told, but also, I mean, it's quite beautiful to look at, as well. And so I felt slightly bewitched by it, and obsessed by it – I became very quickly obsessed with all things Cambodian. So I ended up, I remember, I must have gone and seen the film in the cinema at least 20 times.

Partly, Nic admits, the film took him away from his London experience, when he was still unhappy about his family’s move.

NIC: So I was desperate to learn more about the Khmer Rouge where they came from, why they did what they did, and learn about the country itself. And I think the one thing about “The Killing Fields” that was nice - unlike a lot of the other films about the American experience of Vietnam - is that you got a sense of a country being destroyed. Not just a war, but a country. And it was, fairly evenly balanced between the western perspective and something of the Cambodian experience.

Like I told you in this podcast’s “Journos” trilogy, “The Killing Fields” is also one of the all-time great journalism movies.

NIC: I think it was also this idea of first time I'd ever really thought about journalism, you know, thinking about people who actually bother to go out into the world and see things and explore things and try and understand things and try and bring that understanding to people who don't have the opportunity.

Having dropped out of art school, Nic launched his freelance photography career, basing himself in Bangkok, Thailand. He traveled into Cambodia on a regular basis throughout the 1990’s.

In his camera bag, more often than not, was that photo of Comrade Duch. He often asked around about him.

NIC: One of the things that’s quite interesting is that there were rumors of Duch’s whereabouts - there were sort of whispers. I didn't think for a moment that he would be there.

It’s 1999 - 10 years since Nic visited Tuol Sleng for the first time.

You need to know Cambodia is one of the most mined countries in the world. Every group of fighters laid landmines - the Khmer Rouge, government troops, the different factions –throughout the decades of fighting. No one ever bothered to map their minefields, or dig the mines up again. So people still get blown up by decades-old landmines to this day.

Nic was hired by the Canadian government to shoot demining operations they funded in a remote part of western Cambodia. This is Samlaut district – then about 2 hours southwest of Battambang, on horrible roads. It’s the place where the Khmer Rouge movement was born in the late 1960’s.

It’s also the place many of the group’s most brutal killers fled to, when the Khmer Rouge were overthrown in 1979. It was one of those zones I always thought of as government-controlled by day, Khmer Rouge-controlled by night.

The Canadian deminers had a logistics meeting that Nic had no reason to shoot.

NIC: I was wandering around. I mean, it wasn't part of their entourage in that way. That this small and wiry man walked up to me and introduced himself with the name of Heng Pin. And, you know, he's a very striking individual. I mean, there's no doubt in my mind, it was Duch.

Remember, the Khmer Rouge were always paranoid and secretive. Nic was in Samlaut – a district awash in fugitive war-criminals. So he knew better than to call Duch out by name.

In fact, talks were underway at this point between the United Nations and the Cambodian government to hold the Khmer Rouge war-crimes tribunal. Prime Minister Hun Sen - himself a former Khmer Rouge officer - didn’t want that to happen.

Still, Duch spoke reasonably good English – and he was the one who walked up to Nic. So Nic kept chatting. And fact-checking.

NIC: We talked a little bit and I thought to myself, this is kind of weird, that he should walk up to me in the end. And I thought to myself, you know, you know, that sort of thing where you you know, you can't quite believe it, but you think to yourself, Well, why not? I mean, why shouldn't it be him? Anyway, I talked to him a little bit, I managed to find out that he used to be a teacher, that he taught mathematics. And he was from Kompong Thom. I think those are the only facts that I managed to establish at that stage. And I thought, Well, I'll try and get a picture of him, which I did manage to get a photograph he was quite reluctant to. But he was wearing an ARC t shirt. So American Refugee Committee because he'd been working with them in a refugee camp on the border. And I took a photograph of him. And I think I asked somebody if you live nearby, and they said that he did.

Nic knew he had made a major discovery. One that was also dangerous.

NIC: Nobody had heard anything from them since he left - fled Phnom Penh in 1979. That's all we knew of him. Nobody had heard from him or since. I didn't know that stage when he was still head of the secret police and still killing people. I had just no idea.

Nic went back to Bangkok and met with some colleagues, from APTN, the tv division of the Associated Press. They compared Nic’s old photo from Tuol Sleng with the one he just took, and agreed:. Thist has to be him. I’ll post some links on the webpage.

Soon, Nic headed back to Samlaut with a friend, American photographer Stuart Isett. Nic had a small video camera that APTN had given him. Once again, they were able to track down Comrade Duch.

It was still incredibly dangerous to try to do an interview about Duch’s past. So Nic walked him out of earshot of everybody else nearby. He asked him about the aid-work he did.

NIC: I saw him. We introduced each other we chatted with Stuart, and then Duch and I went for a walk up the road to visit refugee families. And that's when I did a short interview with him. It’s at that point he had confessed that he was a Christian. And he seemed very pleased with us. And you know, he's very ingratiating. I mean, I don't know if you remember him in his trial, but he clearly is very, very aware of where people were on the hierarchy. And he thought I'd be very pleased to know that he was a Christian.

Nic and Stuart got out of Samlaut with their material as quickly and as quietly as they could. Nic still hadn’t tipped his hand that he knew who Duch was.

Back in Bangkok after his second trip to Samlaut, Nic pitched a story about finding Duch to the Far Easten Economic Review, a weekly news-magazine. Their regular correspondent was American journalist Nate Thayer.

NIC: The Review came back to me and said, “Look, great story. This looks like him for sure. But we'd like you to go back and give him the opportunity to defend himself.” So Nate said to me, “You know, I'd love to come for the historic record. I mean, it's your story, but I'd love to come.” So he did.

A quick word about Nate.

Nate Thayer was a minor celebrity in Southeast Asia’s press circles. In 1997, he was the guy who found Pol Pot, the head of the Khmer Rouge. Pol Pot, of course, was one of the worst war-criminals of the 20th century.

Like Nic, Nate was fascinated by the Khmer Rouge. He spent more than a decade as a reporter infiltrating the Khmer Rouge movement.

Nate’s story deserves to be told in its entirety. He was a friend - and he died in earlier this year.

For now, what you need to know is that Nate had interviewed Pol Pot. He had also interviewed Ta Mok, another top Khmer Rouge leader.

These made headlines around the world. And that includes in the Khmer-language news services of Voice of America and the BBC. Those are shortwave radio broadcasts. That means even in places as remote as Samlaut, people knew the name, “Nate Thayer .”

In Samlaut for a third time, Nic – with Nate along - tracked down Comrrade Duch.

NIC: We sat down to talk. That’s when I think it was put to him three times, you know, that we believe that you were head of the Khmer Rouge Special Branch, or you ran Tuol Sleng, or whatever. And three times he deflected.

This trip was no less dangerous than the previous two. Nic and Nate were challenging a fugitive war-criminal, known to have killed thousands, to his face. Journalism requires they confirm that Duch was who they thought he was.

NIC: Nate and I had already sort of rehearsed this and thought about what - Okay, What - what are we going to do if he doesn't confess? So what we decided to do is that we would get him to write a letter to a doctor that he worked with on the Thai-Cambodian border in a in a refugee camp. And we said we'd happily deliver it to him … Then at least we'd have a sample of his handwriting, we could compare it with the notations from the documents from S-21. Anyway, it was while he was writing this letter to this doctor that he looked at Nate's business card. And then he realized that, he said that, I believe your friend has interviewed Messieurs Pol Pot and Ta Mok. And I said, “That's right.” And that's when the penny dropped. That's when he realized the real reason we'd come. And that's when he began to talk.

Remember, Duch had become Christian.

As Nic writes in his book, Duch said, “It’s god’s will that you are here. Now my future is in god’s hands.”

Suddenly, Duch was giving an interview - spilling secrets - to Western journalists. To the Khmer Rouge, that’s reason for execution.

What ensued now was a high-stakes games of cat and mouse. This is worth a podcast episode in and of itself, but this is the short version. Nic had to leave Samlaut, to file his story for APTN.

Within hours, someone threatened Duch’s life. So Nate offered to hide Duch in a hotel room, two hours away in Battambang, to do an extended interview.

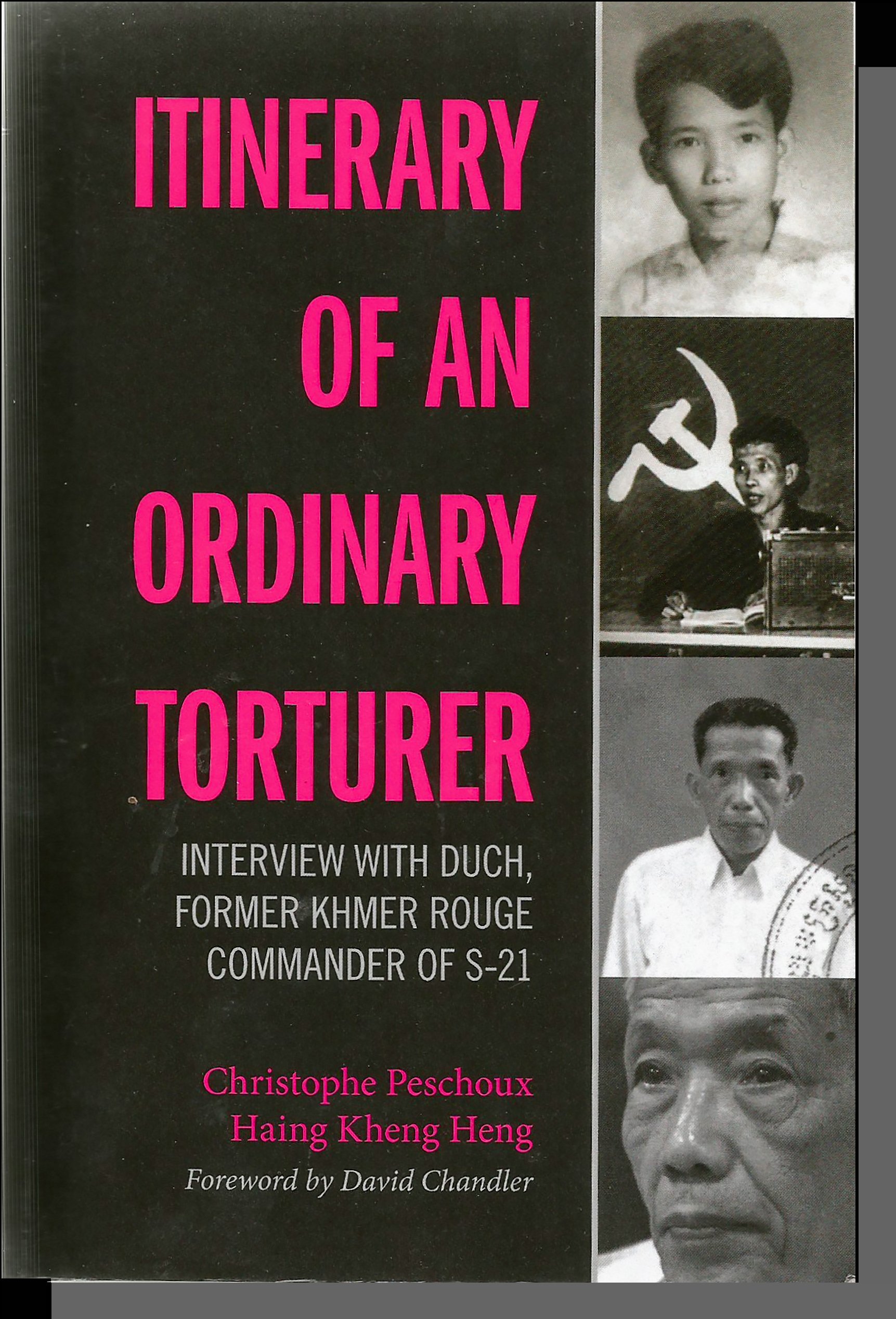

Nate also brought in Christophe Peschoux, from the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights. Peschoux’s book, “Itinerary of an Ordinary Torturer” is where I’m getting some of these details.

Nate, Peschoux and a translator interviewed Duch extensively over the next three days. That would later become part of a legal dossier at Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge tribunal.

Duch’s life was still at risk. The interview complete, he nonetheless chose to leave that Battambang hotel and the relative protection of Nate and Peschoux. He was soon arrested by the Cambodian government.

Christophe Peschoux’s book of his interview with Comrade Duch that eventually formed part of a legal dossier at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts f Cambodia - the Khmer Rouge tribunal.

To this day, I don’t understand why Duch wasn’t murdered, and neither does Nic. The Khmer Rouge now hated him. Prime Minister Hun Sen didn’t want a tribunal to take place, and here was Duch spilling secrets. Hun Sen could have had easily had him killed by a government agent.

The UN had issued a communiqué calling for Duch’s safety, according to Peschoux’s book. And apparently Amnesty International was also brought into the loop and they issued a press release. But still.

MPN: It just amazes me that that man lives tell the story in court.

NIC: Yeah. I don’t know that that those that NGO folk would have that much clout, I just don't know.

Anyone involved in this process – Christophe Peschoux, Thomas Hammemberg, someone from Amnesty International or Hun Sen’s office – I invite you to get in touch.

Instead, Comrade Duch lived to tell his story. More than that, he went on to turn state’s evidence against the senior Khmer Rouge leaders – as Case Number One – at the Khmer Rouge tribunal.

Thank you for listening. In the next episode we’ll hear more about the Khmer Rouge tribunal; and what Duch said about the Haing Ngor murder, and why Nic and I think it was complete and utter nonsense. We’ll also hear Nic’s reflections on what the Khmer Rouge tribunal and what Duch’s testimony meant to a Western audience, and what it meant to Cambodians.

That’s coming up in the second episode of “Finding Comrade Duch,” which is Episode 10 in the “Who Killed Haing Ngor” podcast.

My name is M.P. Nunan. Remember, this is a crowd-sourced podcast – an experiment in journalism.

If you knew Haing Ngor personally and would like to contribute – even just an interesting anecdote - please get in touch. If you know any details about his murder you think are relevant, please get in touch. The best way to reach me is to email whokilledhaingngor@gmail.com

Haing is Ha I ng

Ngor is N G or