Episode 02: The Mayor of Bamboo City

Welcome – this is episode 2 of “Who Killed Haing Ngor,” a real-time and crowdsourced podcast in which we explore the lingering questions about the murder of the Dr. Haing S. Ngor, the doctor, political activist, and actor who’s probably best known for his role in “The Killing Fields.”

Today I’m sharing parts of my recent conversation with Andy Pendleton, an aid-worker whose resumé reads like a catalog of contemporary war and political crisis.

Among his deployments? Darfur, the Rohingya Crisis, Cameroon, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Covid – and a vast amount of work in Cambodia, as it transitioned from the nightmarish days following Vietnam’s 1979 invasion toward something resembling peace.

Often at work for United Nations agencies, Andy’s the aid-worker in charge of security and coordinating the operations of all the aid-groups and non-governmental organizations operating in a given crisis. Andy was so well known on the Thai-Cambodian border, with its makeshift, temporary and tropical housing that he earned the nickname, “The Mayor of Bamboo City.”

Andy’s the guy you want with you in the trenches. That’s how he came to meet Haing Ngor.

And full disclosure: Andy Pendleton is a friend of mine. I caught him at home in Virginia.

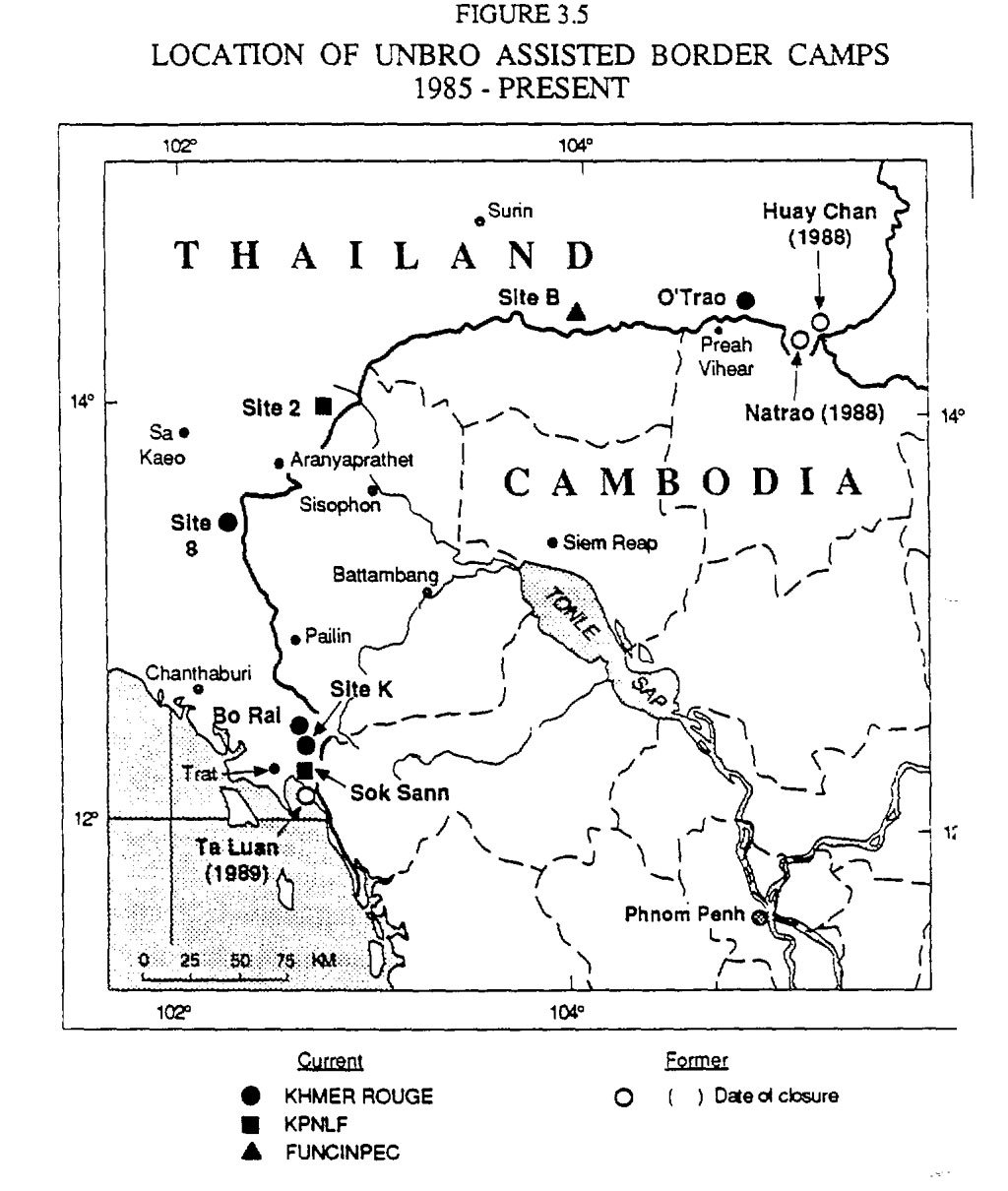

A quick history recap: The Khmer Rouge, headed by Pol Pot, took control of Cambodia in April 1975. Nearly four years later, in January 1979 – Vietnam invaded, forcing the Khmer Rouge from power.

Senior Khmer Rouge and thousands of their fighters retreated to remote pockets of territory along the Thai-Cambodian border. Cambodia’s Wild West. Hundreds of thousands of ordinary Cambodians also fled for what would become a constellation of refugee camps – also along that same border. They were in search of safety, in search of help, in search of food - given the starvation, the atrocities, and the nation-wide devastation wrought by the Khmer Rouge.

You’ve heard the term, the “fog of war?” It was thick along the Thai-Cambodian border in 1979 and into 1980, when 25 year-old American Andy Pendleton showed up with a Baptist missionary group.

Above, Andy Pendleton at Site I Refugee Camp, as Senior Camp Officer for UNBRO, during Vietnam’s 1984-1985 offensive.

Second photo: Andy with John J, Moore, UNBRO’s Field Director; Site I

Third photo: Andy pointing out an artillery strike outside Site I camp; circa 1984. Photo by friend Nate Thayer, who made him smile. Photos courtesy of Andy Pendleton.

ANDY: We believed the Khmer Rouge were the victims, because that’s what they had told us. … We believed what these Khmer Rouge base people and leaders had told us that they in fact, were the victims of the Vietnamese they committed the atrocities. And we bought it. … In fact, I remember one day at a UNHCR meeting. I had a girlfriend - she was French. And she showed up with a completely Khmer Rouge uniform on. She had on the Khmer Rouge hat, the scarf, black sandals - she had on everything. And, and it was like we were part of them in a way. It was really, really bizarre if you look back on it now.

It was “Year Zero,” the 1977 book written by French priest François Ponchaud about the Khmer Rouge brutality that was first to pop that bubble for Andy. That and the 1979 documentary of the same name by British journalist John Pilger. Andy would learn that the Khmer Rouge were a demented, genocidal death cult – just not at first.

ANDY: And I studied very hard - for two and a half years - I got so I did not need a translator in Khmer. And when I moved to the Khmer Serey, the free or non-communist refugee camps… somebody walked up to me and said, “You’re speaking in the Khmer Rouge dialect.”

And I went, “I'm sorry?”

And they said, “Yeah, the words you speak. You're speaking the way Khmer Rouge speak.”

And I went, “Really?”

He said, “We don't talk like that here.”

And I went, “Uh oh.” And what I'd realized is we couldn't see the forest for the trees . We thought the KhmerRouge were quite alright.

Andy and his colleagues were far from alone. Prominent academics also fell for the Khmer Rouge line. That sparked a feud among Cambodia scholars that actually still lingers to this day.

It wasn’t like now – in a conflict like Ukraine, Syria, Afghanistan or Myanmar – cellphone cameras, YouTube, social media, text messaging -- all of that allows for documentation of war-crimes – almost in real-time. In fact, in policy and human rights circles these days, you hear about the over-documentation of war-crimes in Ukraine. There’s actually a redundancy of investigations into certain incidents.

But In the 70’s and 80’s, no one had a secret cellphone stashed away to upload evidence of the atrocities. Nor were Khmer Rouge fighters posing selfie videos, cut against bad hip-hop with too many cheesy dissolves - boasting of battlefield victories, and giving away their crimes, like ISIS does.

Back then, it wasn’t until the Khmer Rouge withdrew from a camp that ordinary people felt free to speak.

ANDY: They just poured out stories of how they've been killed and slaughtered and tortured and everything, so we became very well aware of it once the Khmer Rouge left themselves.

In 1983 Andy had moved on to UNBRO, the United Nations Border Relief Operation for what would become some defining years of his career.

The Khmer Rouge weren’t the only armed faction to control refugee camps and to fight in the civil war. I’ll skip the alphabet soup of acronyms for now, but they were “royalist” fighters and a self-proclaimed “liberation” front, forming two “non-communist” armed factions.

It was also the Cold War. China funded the Khmer Rouge. The US meanwhile was funding the non-communist groups against the Vietnamese. In Cold War logic, that makes perfect sense -- communism: bad. But that’s only if the US stopped there. Washington actually funded the Khmer Rouge – communist fundamentalists – because the US was still overwhelmingly pissed off at Vietnam, which had sent US troops packing just a few years before. They didn’t want Vietnam to expand its power by turning Cambodia into a protectorate; a vassal state like it was trying to do. And the Soviets? They were on the side of Vietnam.

So Cambodia was a proxy war between the Great Powers, again - just like Syria and just like Afghanistan. The refugee camps were pawns.

MPN: And how many camps were there altogether?

ANDY: Oh my goodness. Once they were recognized by the UN… 9 recognized by the UN but an additional 26 others and an undeterminable actually amount were hidden base camps…. But In essence, the problem with the camps is that the guerrillas conducted warfare from the heart of these camps. and the Vietnamese knew that. And so when they conducted forays right out of the refugee camps, the response to that would be to shell the camp. And so needless to say, it’s pretty horrific when refugee camps get shelled indiscriminately . You've got massive amount of wounded and evacuation going on.

For the record, shelling refugee camps in that manner, even if there are guerrilla fighters hiding inside – is a war-crime.

ANDY: It was a very different time and UNBRO was a very brassy organization. We would actually leave the refugee camps under a blanket of artillery shell fire to safe haven in Thailand. Very brassy.

MPN: And how many how many times did you have to?

ANDY: I did that seven times. UNBRO did something like 54 times during the dry season offensive at 84-85.

1984 – that’s when “The Killing Fields” came out, and 1985 is when Haing Ngor won his Oscar.

With the weight of celebrity behind him Ngor teamed up with Dith Pran, “The New York Times” assistant reporter, upon whom the movie is based, to push Washington and the United Nations and other powers for more assistance to the camps.

The Ronald Reagan Presidential Library has released footage of their meeting with the former President on YouTube, which I’ll put up on whokilledhaingngor.com.

Haing Ngor, Dith Pran and guest meet President. Ronald Reagan in the Oval Office, May 24, 1985.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yyaCnM7jhb0

Perhaps not surprisingly, Haing Ngor soon visited the Thai-Cambodian border. It was 1988. Andy knew who he was – in fact, the film’s casting agents had visited the camps looking for fluent Khmer speakers to play small parts in the movie, which was shot in Thailand. Andy didn’t get picked. But when bootleg VHS copies of “The Killing Fields” began to circulate, he and his UNBRO friends all managed to see it.

By now, Andy had won his nickname, “The Mayor of Bamboo City,” for his work in the Site II refugee camp. With close to 200 thousand people, Site II was the second most populous Cambodian city – only it wasn’t it in Cambodia. It was in Thailand.

And that’s where Ngor came to speak – and speak his mind actually, about the Vietnamese, and about how Cambodian leaders at all levels were failing the refugees.

ANDY: We had this idea. And he was very vocal. He was a real advocate. And he was himself just sort of fed up with corrupt leaders, and fed up with all this. And he wanted to make a difference. And he had a lot of brass. And so - I didn’t know he had that much brass! But we invited him to speak on Human Rights Day in Site II and he got up there on a microphone and he let everybody have it. The last, the last targets where the Khmer leaders of the camp itself - and he blasted them. After he was finished with them and their corruption and their selfishness and everything else, he was just about done. And so people came to me and said, Look, you better get him out the back way, man. This guy just put himself in lot of heat here. He didn’t pull back on anybody – he blasted them all.

MPN: Was his visit useful?

ANDY: You know one thing, it allowed a Khmer to come into Site II to let off the chain and blasted everybody – and it was never done before. And it was never done after. And people loved it.

MPN: He said what a number of the refugees were thinking in terms of how the camps were being run and corruption and being sick and tired of being a refugee?

ANDY: Oh, yes - absolutely. Absolutely. He got top marks that day, I’m telling you.

MPN: And did people respect him at this time because of the movie or did they think of him as oh, Mr. Hollywood?

ANDY: I'm not sure how much they recognized him as that. I'm not sure how many how many bootleg copies were in the camp and so on. After that, yes, but before that, I'm not sure they knew entirely who he was. But they knew one thing, he wasn't afraid to talk and he spoke his peace.

But I threw him my car after that. I was the master of ceremonies. And I went ahead and finished. and I put him in my car. And I was one of the few people that could take the back way out. The Thais didn't mess with me. We went into Aranyaprathet, [Thailand] and had dinner and had a few beers together. I enjoyed his company, and we met in Phnom Penh later as well.

Andy Pendleton as Master of Ceremonies on Human Rights Day in Site II Refugee camp. 1988.

Photo courtesy of Andy Pendleton.

Peace broke out – kind of – in 1991. Cambodia’s four armed factions, including the Khmer Rouge, signed a peace deal ushering a massive UN peacekeeping mission into Cambodia the following year. That’s when I showed up, starting my journalism career.

It was an incredibly hopeful time. I don’t have exact figures, but probably thousands of Cambodians who had resettled overseas in places like Long Beach, California came home. They wanted to see family, to start businesses and to rebuild the country. Cambodia was meant to be turning into a democracy.

Andy by now was with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. Ngor dropped in on Andy one day in 1993, when he happened to be in the capital, Phnom Penh.

MPN: Was that a social call?

ANDY: Social and professional. He wanted me to brief him on the refugee situation. He wanted to know about the people in Site II and where they've gone. And so we pulled out some maps and resettlement pattern maps. We looked at the demographics and stuff and I didn't have a whole lot of time that day, but I just pushed it all to the side and talked with him.

And he really appreciated it. The next time I saw him, it was in the Royal Phnom Penh Hotel – that’s when I saw him with the diamonds and the jewelry with a lot of very wealthy looking Chinese people.

Ngor was murdered in Los Angeles in February 1996. Three members of the Oriental LazyBoyz gang were convicted and went to prison or killing him.

ANDY: I was horrified. So disappointed and sad. I just didn't understand why and there were rumors flying everywhere. So I never really understood what had happened.

MPN: Because I'm chasing up leads, can you tell me what were the rumors that you heard about the murder?

ANDY: Owed people money, went over his head. I saw him a couple of times in Phnom Penh….He had a lot of gold and diamonds and stuff on. I don't know - it's up to him. But you know, I think that he had he had such passion to make a difference. And he didn't care almost if he put his life at risk to do so. But when he came into Phnom Penh, I saw the people he was hanging around with, they all looked like they were loaded. And we were saying, we were hearing, he's just in way over his head. And he made good money - but he got into investments and he borrowed money. And we heard that the Chinese mafia knocked him off.

Those are the rumors. Ngor had gotten tangled up in illicit Chinese money and this was a contract killing. Those rumors made it into local news stories about the murder – I’l put a link on the webpage to an article in the Phnom Penh Post, a prominent English-language newspaper at the time. The outspoken Ngor was characterized as a polarizing figure. Still, the Post says, some people wanted him to make a political run – offers he reportedly turned down.

Andy doesn’t know for sure what happened - and at this point, neither do I. But I think those questions deserve more attention.

ANDY: Funny. Friendly. Polite. Generous. And of course, I have relatively limited exposure to him. I mean, we got to know each other pretty well of those three or four times but these are just my impressions and - I really liked him. I like his brass. I like his outspokenness. I like what he what he stood for that day in Site II. And I don't know - I admire the man. It's all I can say.

Thank you for listening. My name is M.P. Nunan. Remember, this is a crowd-sourced podcast – an experiment in journalism. If you knew Haing Ngor personally and would like to contribute – even just an interesting anecdote - please get in touch. If you know any details about his murder you think are relevant, please get in touch. The best way to reach me is to email whokilledhaingngor@gmail.com

“Haing” is H-a-I-n-g and and “Ngor” is N-G-o-r. Thanks again.